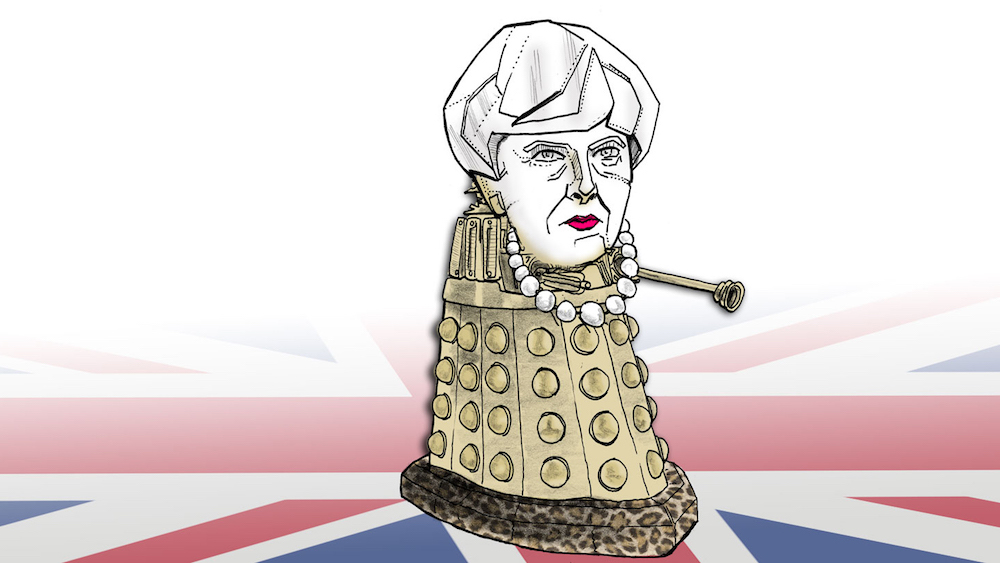

Theresa May was best when she didn’t talk at all. Once she started speaking, she turned out phrases like “Brexit means Brexit,” giving rise to a damning nickname. But despite all her robot-ness—May is here to stay.

A curious phenomenon marked the weeks that followed David Cameron’s resignation on the day after the 2016 EU referendum. While all the other hopefuls took to the airwaves, Theresa May managed to remain nearly silent. One by one, her rivals eliminated themselves from the contest by saying something catastrophically stupid, until May was the last person standing. It was the first time in British history that someone had become prime minister by shutting up. Whether by accident or design, it was a stunning piece of political gamesmanship.

What was so effective in getting her through the doors of 10 Downing Street, however, proved less helpful once she was ensconced. A prime minister cannot get away with saying nothing indefinitely, and eventually, May had to try out a few phrases. The most common of which was “Brexit means Brexit.” While a few of those who had been enthusiastic about Britain leaving the EU took “Brexit means Brexit” as a sign of intelligent life, the rest of the country began to wonder if there was even less to May than met the eye.

When May began answering completely different questions to the ones she had been asked in every interview, I dared to think her brain might have been hacked and taken over by malware. Ask her what “Brexit means Brexit” really meant and she would invariably whirr into inaction and say, “I am determined to be focused… (she wasn’t; she really wasn’t) … on the things that the British people are determined for me to focus on.” The Maybot was born.

The idea of May as Maybot came to me while watching the prime minister give an interview to Sky News when on a trade trip to India. Her speech patterns were slow, robotic and faulty and you could almost hear the out of date motherboard creaking in the background. This wasn’t a sleek top of the range Apple Mac: rather the prime minister had modelled herself on an obsolete 1980s Amstrad.

Political sketch writers come up with a lot of names for politicians—I also referred to the prime minister as Kim-Jong May because she appeared to be the Supreme Leader of a failed state — but Maybot seemed to capture her perfectly. Not just her inability to hold meaningful one-to-one conversations, but also her lack of warmth and charm. Given the choice of talking to a person or a wall, the Maybot would invariably pick a wall. The name stuck and it wasn’t long before even right-wing, pro-Brexit publications were calling her the Maybot in print.

An Illogical Machine

Things never really improved in the first eight months of her time in office. First, her government lost its case in the Supreme Court over its refusal to allow parliament a vote in triggering Article 50. May was not at all happy about this: Britain hadn’t voted to take back control in the EU referendum only to allow the British parliament to have a say in how the country was run. She appeared to be even more angry when the Labour Party chose to thwart “the will of the people” by voting with the government to trigger Article 50. Logic never was the Maybot’s strong point.

Despite all these very obvious shortcomings, the Conservatives still held a twenty-point lead over the Labour Party in the opinion polls and immediately after the Easter break, May announced she would be holding a snap general election—despite having explicitly stated on seven previous occasions that it wasn’t in the national interest to hold a general election. Some people began to wonder if the Maybot was getting confused between what was in the public interest and what was in her own.

The early weeks of the election campaign were characterized by Theresa May going round the country saying “Strong and Stable” in front of a small group of Conservative party activists who had been herded into one corner of a community center to make it look on TV as if she was playing to sell-out audiences everywhere. Things didn’t improve with the launch of her manifesto. Within days she was forced to insist that “nothing has changed” as she changed pretty much everything.

She couldn’t see for the life of her why everyone was calling her dementia tax a tax on dementia just because it was a tax that targeted people with dementia. Besides which her manifesto had never been meant to be seen as a list of electoral promises; rather it was just a series of random ideas formed of random sentences. It was around this time that even her advisers started calling her “The Maybot.” The name seemed to describe her so well. Awkward, lacking in empathy and—above all—not very competent.

Despite all this, the Conservatives still held a large lead going into polling day with May expecting to gain a majority of sixty to eighty seats. The electorate saw things differently. Having been asked to back the prime minister and give her a strong mandate, they instead chose to give her no overall majority. The Maybot was devastated and the Tory party were far from impressed.

Ordinarily, she would have been forced to go as leader within a week, but these were desperate times. The gene pool of talent within the Tory party was so small, there were no obvious replacements. Besides which, the last thing the Conservatives wanted was another election as they would probably lose. So her punishment for failure was being forced to stay on as prime minister.

“Rong and Stale”

Over the summer May decided to lay low, licking her wounds and hoping no one in her party would launch a leadership bid against her. Come the party conference in October she was ready to reboot herself. Only Maybot 2.0 looked to all intents and purposes much like Maybot 1.0. She had meant to convince the party she had learned from her mistakes but her apology for her election campaign being too scripted just sounded… too scripted. Then comedian Simon Brodkin made his way to the stage to give Theresa her “P45”, a redundancy note. Then her voice went into revolt and refused to speak. The nadir was the frog leaping out of her throat and on to the screen behind her where it started knocking off the slogans. “Strong and Stable” became “Rong and Stale.”

Then May realized that maybe it had been a mistake to leave David Davis in charge of the Brexit negotiations. Having told a select committee that his department had been making in-depth impact assessments on 58 sectors of the economy, the Brexit secretary was forced to admit that the assessments did not actually exist when he was asked to produce them. At which point May headed over to Brussels to take charge of the negotiations. Unfortunately she had forgotten to inform Arlene Foster, the leader of the DUP on which she relied for her majority, and was then forced to tell the EU that she wasn’t able to agree to the deal she had come over specially to sign.

Eventually the EU took pity and came to her rescue. Better to deal with a fatally wounded Maybot whom they could at least vaguely trust than risk her being sacked by the Tories and being replaced with someone even more incompetent. So the EU signed off the first phase of the negotiations—even though no one could quite agree on what had been agreed—and gave the green light to the second phase.

The Maybot momentarily forgot that three members of her cabinet had been forced to resign, that the National Health Service was in crisis, and that UK productivity was among the lowest of all G20 countries and celebrated as if she had won the lottery.

So what if it had taken the best part of a year to conclude the really simple part of the Brexit negotiations and she had left herself under a year to deal with the really tricky stuff? So what if her party—and the country—were still as divided on Brexit as they had ever been? So what if she still didn’t really have a clue what final Brexit deal she even wanted? She may be useless but there was still no one obviously better in the Conservative party. There is life in the Maybot yet.