Since right-wing populist parties began gaining power in Europe and the United States, common wisdom has held that their success is owed to the economic hardships endured by their voters. Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) is theoretically fueled by the comparatively poor economy in the country’s former East, UKIP’s voters are frustrated with the lack of development in England’s small post-industrial towns, and, across the Atlantic, Trump’s popularity stems from frustrated rural voters who have not felt the benefits of the economic recovery.

The problem is that none of those arguments gels with reality—neither with the economic realities of the regions concerned nor with the subjective realities that emerge from surveys. In fact, according to a survey carried out by the German Savings Bank Finance Group between May and July, Germans are just about as optimistic about their country’s economy as they’ve ever been: 63 percent described their financial situation as “good” or “very good,” better than in any year since 2001. This optimism includes Bavaria, where 68 percent were satisfied with their financial outlook—and where voters recently delivered the governing CSU party its greatest defeat since 1950, while the AfD won enough votes to become the fourth-largest party.

A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center from October to December 2017 may shed some light on the forces that are actually propelling populist parties higher. There is indeed some evidence that economics plays a role: right-wing populists in Germany were eight percentage points more likely to earn below the national median income than the center-right; right-wing populists in Italy were nine percentage points more likely.

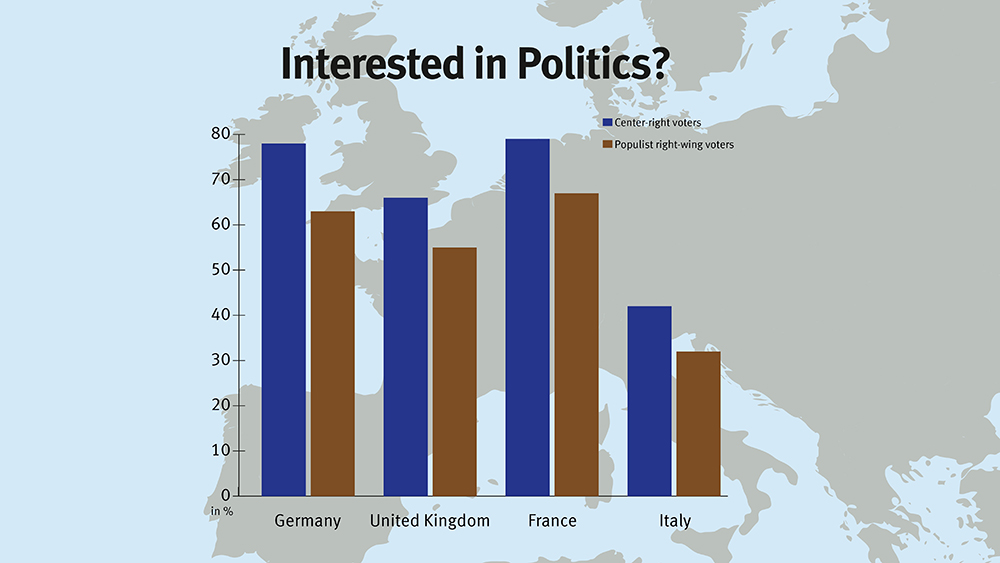

But the starker difference was in political engagement. Right-wing populists in Germany were 15 percentage points less likely than center-right Germans to say they were at least somewhat interested in politics; right-wing populists in Italy were 10 percentage points less likely, right-wing populists in the UK 11 percentage points less likely, and those in France were 12 percentage points less likely.

Why are these voters tuning out? The answer may have as much to do with their trust in their political representatives as with economics. In Germany, 62 percent of people who held a favorable view of the Social Democrats, or SPD, said they trusted the country’s parliament “somewhat” or “a lot,” as did 66 percent of respondents with a favorable view of the CDU and 66 percent with a favorable view of the Greens. Among respondents with a favorable view of the AfD, however, only 35 percent said the same—and 37 percent said they didn’t trust parliament at all. Meanwhile, 51 percent of those who had a favorable view of the AfD said they didn’t trust the media “much” or “at all.”

These numbers varied from country to country—UKIP supporters, for example, had more faith in the British parliament than Labour voters, possibly due to the fact that the UK government is visibly (if badly) attempting to implement Brexit; and Italian and British respondents in general distrusted the news media, regardless of their political inclinations. The German example is particularly helpful in light of the political drama the country has experienced over the last year. Even as leaders in the political mainstream have struggled to contain the AfD, they’ve simultaneously been locked in a number of squabbles within and between parties, from the perennial will-he-stay-or-will-he-go act of Interior Minister Horst Seehofer to the recent back-and-forth over the president of Germany’s domestic intelligence service, Hans-Georg Maassen. If German voters with a favorable view of the AfD are predisposed to distrust the parliament, constant infighting within the body itself is unlikely to help.

It’s difficult to say what exactly engendered this mistrust, but it may well be tied to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s everything-to-everyone reshaping of the CDU. In order to grow her party’s base, Merkel has adopted and amalgamated policies that are generally popular, regardless of how well they fit in with traditional conservative CDU values. Doing so has allowed her to win four terms as chancellor—but at the same time led many voters to ask what exactly it is they’re voting for when they vote for Merkel’s party. A vote for the CDU is a vote for stability, rather than for or against any particular policy.

After the federal election in 2017, many German political observers predicted that another “GroKo” government—a “grand coalition” between Chancellor Merkel’s CDU and the Social Democrats—would be the death knell of the SPD, which has struggled to demonstrate to its working-class constituency that it’s still serving their interests while operating within a center-right government. The critics haven’t been disappointed: The SPD has, rather embarrassingly, dropped to third place behind the AfD in several recent national polls. But with the collapse of the CDU and CSU and the continued ascent of the AfD, it’s becoming clear that the coalition isn’t serving either party well—and that, difficult as it might be to believe, German voters might prefer clarity and credibility to stability.