No bilateral relationship is closer than that between Germany and France. Yet it is still often said that relations need to be closer and more harmonious. A conversation with the Deputy Directors of Policy Planning Staff at the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, ALEXANDRE ESCORCIA and SEBASTIAN GROTH, on day-to-day cooperation, engines, and romantic couples.

Mr. Escorcia, you describe your relationship with Germany as an “old love story.” In what way?

Alexandre Escorcia: When I arrived in France at the age of eight, I had a “migration background,” as it is called in Germany. I’m originally from Colombia. So I didn’t need to study Spanish as a foreign language at school. Instead, I chose German, which I really enjoyed. But the real breakthrough came later, during my diplomatic training. I spent three weeks in Germany and being able to work together with German colleagues made a big impression on me. As neighbors, our countries are very close in many respects, but there are also huge differences when it comes to culture and our views on the world. I later became an exchange diplomat at the Foreign Office, and then did a long stint at the French Embassy in Berlin. In my current position, I take every opportunity to work on areas that bring together French and German perspectives. That’s the great thing about this cooperation. There’s always a Franco-German factor that can be ramped up or down.

Sebastian Groth: We’re ramping it up!

What about you, Mr. Groth?

Groth: I’m from close to Heidelberg, so France plays an important role there anyway—Strasbourg is just 100 kilometers away. I learnt French at school, and then during my time at university in Cologne, I spent a lot of time in Paris and a year as an exchange student in Montpellier. So I do know the “good life” that Germans associate with France, particularly with the south, but I’ve also experienced the education system and the culture first hand, and made a lot of friends. My most formative experience in France was the four years I spent in Paris as an advisor to the Prime Minister on Franco-German relations and European politics. The most intensive period was under Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault, who is a big fan of Germany and very knowledgeable about the country—he later became Alexandre’s direct boss when he took on the role of Foreign Minister.

Escorcia: The “Germans” in our governmental system happen to be quite unique too, because they’re part of the continuity of the French state. Apart from the military, the employees and advisors that come from the forces, the Germans are the only ones that stay put when the government changes. So in a way, Sebastian represented part of the Hotel Matignon’s institutional consciousness.

Groth: My time there was during what was definitely the most decisive period for France and Franco-German relations. Since then I’ve often had dealings with France back here in Berlin, for example around the time of the Brexit referendum, when the two foreign ministers Steinmeier and Ayrault worked together to sketch out a way forward. And now, as Deputy Director of Policy Planning Staff, relations with France are again a part of my day-to-day work.

You have the same job title—do you do the same work?

Escorcia: Not quite—because the systems are slightly different. In my experience the Germans work more closely with the ministries—their head of policy planning staff accompanies the foreign minister more often than ours does. But we have a lot of opportunities to work directly with the German colleagues and to discuss all kinds of issues with them.

Groth: I see a lot of parallels too, especially when it comes to the way we are integrated institutionally and our size. Most European partners have smaller policy planning departments; sometimes they are attached to the political departments. Our tasks as deputy directors are also relatively similar, because we often do preparatory work—in management, in communication with the house. And the core tasks of the policy planning departments are very similar: considering how to shape foreign policy over a time frame of three to six months, and the dynamics we need to adopt for that—looking forwards and sometimes to the past, too, when we’re looking at how historical developments can inform developments now and in the future.

Escorcia: I spend about 60 percent of my time dealing with Germany. We have by far the most intensive cooperation.

Groth: It’s the same for us, our closest cooperation is with our French colleagues—our relationship with them is also by far the most trustworthy. We sometimes inform each other about discussions in our ministries or about developments that have more to do with domestic policy. That’s important, because despite harmonious relations, there are sometimes dissonances, although these are usually a result of misunderstandings or misinterpretations. Then we make an effort to understand the other side’s position or the dynamic of their discussion.

Is there a typically German or a typically French understanding of foreign politics, or are you on the same page?

Groth: It depends on the context, of course. I would say, when it really comes down to it, we are always on the same page. In the current situation especially, I think that in terms of the big issues, we are very, very close. What fascinates me about the French approach is the courage to come straight out with concrete suggestions, while in Germany we usually have lengthy discussions. The overall concept has to be perfect before we can start trying to carefully refine it here and there. In that sense the French way is much more direct. That kind of approach can sometimes really help to set a strong agenda—that’s how we see it at least. Maybe Alexandre sees it differently. I think we would do well to adopt a bit of that French courage and risk the possibility that, now and again, something might not work out. The French have to deal with that too, but we are always very keen to avoid any kind of failure. In France there is a bit more openness toward taking that risk—and then to fight for something. One impression I got during my time in Paris was that French diplomacy is able to identify certain very clearly defined goals, and then tries to fight for them internationally. In that sense we could perhaps learn a little from France.

Escorcia [laughs]: Yes, some people even say we have the ideas, you have the money.

Groth: Not only that, I hope!

Escorcia: No, but seriously, it’s true that in France we have more of a “diplomatie des coups.” We sometimes make suggestions based on tactical rather than strategic considerations, and then some German partners think the French have a master plan. We normally don’t. The disadvantage of our approach is that we don’t always think about the consequences. And of course our foreign policy fundamentally includes a military component—a difference that means its not always plain sailing with Germany. But on the other hand it’s also important to see that Germany, or rather our relationship with Germany, is also a domestic policy issue in France. The government is constantly under scrutiny from the public over how close it is to Germany. Sometimes it’s not good to be quite so close to Germany; some people in France see that as submissiveness, particularly in the economic sector. But being too distant from Germany can be seen as going it alone. It’s not easy for ministers or the French president to find the right balance when it comes to Germany. In Germany, that’s not the case.

Groth: I think these questions play an important role in Germany, too. Germany’s top politicians always do well to approach France directly and make it clear that French-German issues are important to them – which is of course the case even in terms of European politics alone, and especially in the current climate, in which we all know that the foreign policy sphere is not getting any easier. That was also something we experienced after the Brexit vote. The first reflex was a French-German one, as it has been in other geopolitical and foreign-policy developments. So in Germany, too, our approach to Franco-German relations definitely includes strong aspects of domestic and European policy.

I do think [Alexandre] has a point about the military and non-military components of foreign policy. Of course France is much quicker off the mark when it comes to taking military action and also acting autonomously. Germany is always anxious to act in cooperation with its partners. It’s important to stay close enough to the French approach that we are able to have an influence on certain things. But if you look at recent events, there has not been a single big issue on which we haven’t worked together, from the Normandy format talks on Ukraine to UN and EU missions in Mali. It was a real game changer for French foreign policy to have boosted Germany’s motivation to engage in West Africa of all places. That’s an example of a real convergence of our views, although some differences will probably always remain. Those can’t just be pasted over; they’re dependent on historical and socio-political factors, as well as a result of the governmental system.

Escorcia: I’ve often noticed how quickly we drift apart because of our different systems—centralized versus decentralized governments. That can create greater distance unless we, and others, work consistently to build on areas of French-German convergence. Within both of our systems, not everyone knows their neighbors well enough to trust that some things happen for systematic reasons and not because of anything else. I have had a lot to do with security policy, an area where old mistrust sometimes still prevails, on both sides. What are the French up to in Africa—isn’t that all postcolonial? And in the other direction: what do the Germans want from central Europe, with others and not us? Mistrust can return very quickly and usually it has more to do with the way things are approached than with their actual substance.

Groth: When it comes to Africa policy, Germans have been very quick to say, and sometimes still do say, that every French initiative is basically connected to the country’s colonial past—people argue that France is keen to continue with or reignite politics a la “Francafrique.” I think those accusations miss the point, that period is behind us. It’s much more to do with the common European interests we represent there, in particular in terms of security, development, migration and the fight against terrorism. A lot has happened in those areas over recent years. Apart from that, France’s permanent seat on the UN Security Council means it has a different geopolitical grasp on many of the issues in which Germany is also involved. Libya, Yemen, Syria and so on are discussed again on another level among the P5 or within the Security Council. I think that from next year, when Germany is also on the Security Council, our foreign policy will mesh even more closely.

People have long dreamt of France’s seat on the Security Council becoming more European…

Groth [laughs]: I hope Alexandre’s fighting for that!

Escorcia: Brexit has shifted relations among the Europeans on the Security Council, at least, and we agree that we need to work toward more visibility for the European Union in New York.

Groth: Foreign Minister Heiko Maas once said in an interview that we would interpret the seat in a European way. It will also about strengthening the bonds between Brussels and New York. Particularly for France, as part of the P5, it can be a battle of two souls: on the one hand acting as a national player with its own interests in the security council, and on the other hand to consider its European connections in a way that might be more natural for us than it is for France. But I think that together, we will try and work on that, and there are many interesting suggestions. I think this is a great chance for Europe.

Up to now there has been a lot of talk about the Franco-German engine, or tandem, driving European integration. How smoothly is that engine running at the moment?

Escorcia: That’s an interesting choice of words. The Germans talk about an engine; perhaps because the German car industry is so strong. We prefer to talk about a couple, because we are French. The romantic couple. “Le couple.” But the French “le couple” is also connected to the idea of an engine. “Le couple du moteur” is an engine’s driving force. But “le couple” still mainly refers to a married couple, which suggests that our relationship with Germany, for us, is a matter of the heart. Just as it can be in a marriage, the institution itself and the will to work together is strong, but a bit more romance wouldn’t hurt.

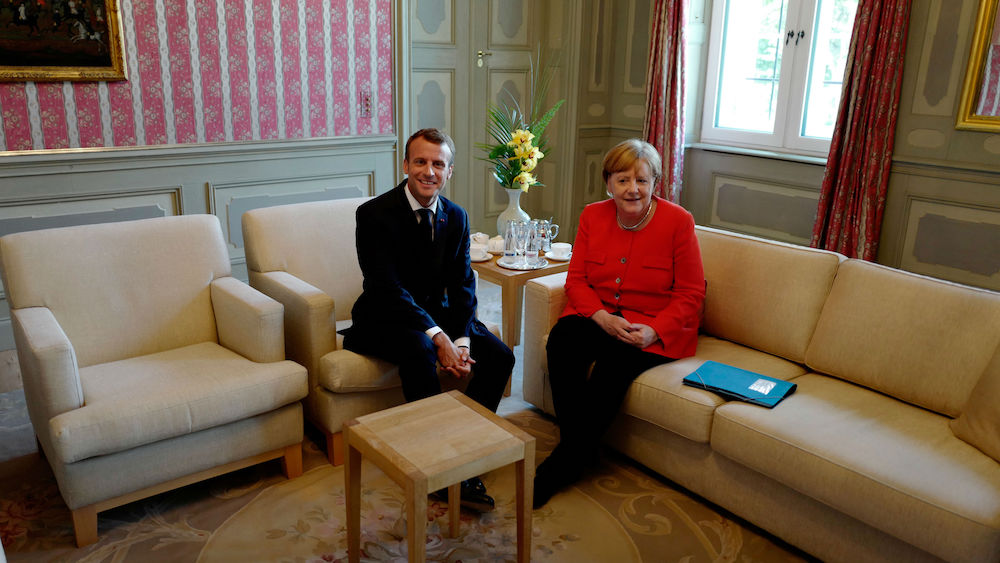

So it’s down to individuals—are things running less smoothly with the Merkel-Macron “couple” than with Schmidt–Gisard d’Estaing or Mitterrand–Kohl?

Escorcia: Individuals always play a role at every level, that’s why I think it’s so important that as many people as possible know the partner country well. From what I’ve seen, people among the German government and civil service know France much better than the other way around. For example, fewer colleagues speak German now than ten years ago.

Groth: The discussion about the quality of the relationship is as old as the relationship itself. Perhaps hindsight casts a rather too rosy glow on many of these old couples. I have the impression that relations are excellent as a rule: for top-level German politicians, their French counterparts are often the first point of contact. And in the lower levels too, in the ministries, coordination with our French colleagues is always the most important. Each of our ministries has, in one way or another; its own department just working on France and our cooperation, so our relations are also reflected institutionally. Still, there will always be questions, and we have to have those discussions when they do arise, because it can happen that we have different opinions. The Euro crisis was of course the big issue from 2010-2014, during my time as an exchange diplomat. People in Paris were wondering why the Germans were approaching the issue in such a juridical, rule-bound way, while those in Berlin were asking why the French were offering such Keynesian and macroeconomic arguments; why, from a German perspective, they didn’t want to do anything more far-reaching for their own competitiveness. These questions and different perspectives will continue to be a part of our work. But even on those issues, I do see a convergence, steps toward common ideas, which we have seen at the Meseberg summit on Eurozone reforms, among other things. There too, the decisive impulse will always come from Franco-German cooperation.

I think Germany will always tend to push harder than France to turn a tactical moment of a common idea into a strategy for as many Europeans as possible. France tends to want to take the step first and would perhaps then look at who can be brought on board. Our planning policy departments have already been working together for a year on a project focusing on the idea of a flexible union, a flexible Europe—which formats, what kind of content can we advance in flexible formats with Germany and France, in foreign and security policy but also in terms of stabilization, economic and innovation policy. We will continue to work on those questions, and the involvement of others. As a rule, I don’t think the psychologizing of the relationships between individuals will get us very far. Our common working ability is stronger than with any other government or foreign minister.

But is there still a certain imbalance, despite that? Macron clearly has higher expectations of Germany than the other way around.

Escorcia: No, I don’t think so. It’s always difficult to bring together the different political calendars. While France is gearing up for an election, Germany is incapacitated and has to wait, and when France is ready to act, Germany is gearing up for an election of its own—that’s how it’s always been. In France we have acknowledged that we have a great partner in Chancellor Merkel—she has the courage to approach us.

Groth: That kind of criticism usually stems from Macron’s Europe speech at the Sorbonne, with his long list of around 70 suggestions. People immediately started asking, what’s happening, what’s the German response to all these suggestions? But when you look at the list, you see that we have already made progress on many things – in part because of German responses and contributions, although our reaction might have taken a while due to the political calendar. But it did come. We didn’t sense any disappointment, perhaps a certain impatience, but that was the case all over Europe until the new German government was in place. I think the Meseberg summit was a really crucial point on that path; the chances are good that we can keep up the momentum and make good use of this period before the European parliamentary elections next spring.

Escorcia: It’s true that the president’s suggestions were very ambitious. But he was not proposing to implement all 70 suggestions in one or two years. He also wanted to get things going.

Groth: And if anyone else has other suggestions, they are of course welcome to present them. The important thing is that the discussion is ongoing and that the aim is to bring ideas forward. The discussion around Permanent Structured Cooperation on Security and Defense or European Intervention Initiatives are good examples—we’ve made good progress there, even if in Germany we aren’t so happy with the term “Intervention Initiative.”

Escorcia: Oh yes. “Intervention!”

Groth: “Initiative” is good, though. We might prefer to go more in the direction of “Initiative for a European Crisis Intervention Team”…

And with that we’re back to the negotiating table.

Escorcia: Yes, we are trying to move our German friends slightly more toward a greater readiness to deploy…

Groth: …And we are trying to encourage our French friends to consider the whole spectrum of action, from military to military-civilian to purely civilian, as an integrated approach—with some success. A few months ago, Macron spoke about a “comprehensive approach” to West Africa, saying military action alone was not enough. Of course that’s not a new concept in France, but I think this area presents many more possibilities for Franco-German cooperation. Not because France has ideas and Germany pays for them, but rather because we both have ideas, both pay and common action makes our policies more effective.

A new Élysée Treaty is in preparation. What should it include—in order to build even better, even more stable relations?

Escorcia: Our policy planning departments have been involved in the discussion…

Groth: … At least in terms of setting the ball rolling at the beginning.

Escorcia: We presented common suggestions – so the policy planning staff’s special channel worked. Now it’s down to the colleagues in the specialized departments to take things forward. But it’s important to mention a few aspects. This is not a replacement treaty, but an additional treaty that supplements the existing one. The 1963 treaty remains the basis of our cooperation. But it needs to be brought up to date in line with the new reality of Europe and new fields of cooperation which in 1963 were not yet in place or not so well developed, from economics to innovation, technology, defense and so on. The basic philosophy is to being a new impetus to our relations, and to the whole European concept. The German-French couple is good for others too. And of course it’s also about preserving flexibility within these new fields and developing our cooperation.

Groth: These are the really key points—what does Franco-German cooperation mean today in a European context? How do we deal with global changes? How can Germany and France work even more closely together on issues like shaping globalization, defending multilateralism and the rule-bound, international order? We’ve already taken a strong stand on climate policy, we are doing the same with trade policy, but there are many other areas where we could develop further. How can Germany and France bring the spirit of the Élysée treaty in the 21st century and make it relevant? That’s what we’re currently working hard to realize.

The talk was chaired by Henning Hoff and Uta Kuhlmann.

N.B. This is a translation; the exchange was conducted in German. The original version can be found here. The English version was first published on September 7, 2018.