China’s rise as a global player is forcing EU member states to rethink the way they pursue their security interests. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), presently chaired by Germany, could become a valuable tool for engaging China on critical security challenges, particularly in Central Asia.

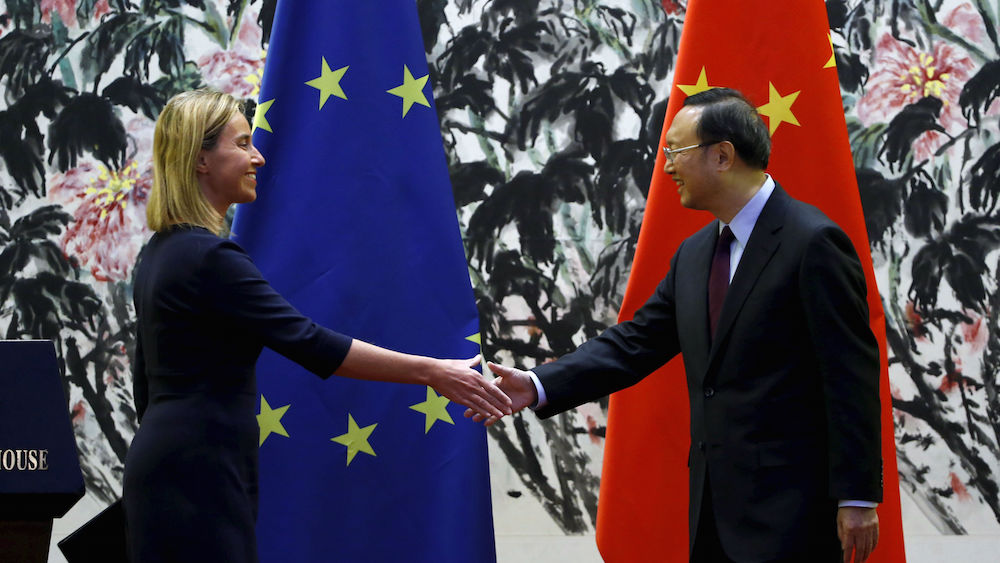

On May 18-19, representatives from participating states and partner countries will gather in Berlin for an Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) conference on economic connectivity. While China is not a part of the 57-member organization, the German OSCE chairmanship has invited senior Chinese officials to join the discussion.

Engaging China on security challenges in Central Asia within the framework of the OSCE could turn out to be a smart strategy for the EU. As China expands its security activities globally, EU member states need to rethink the way they pursue their own security interests. The need is especially pressing with regard to Central Asia, where both the EU and China have high security stakes.

Originally founded as a venue for dialogue between East and West during the Cold War, the OSCE today is an intercontinental forum encompassing the five former Soviet republics in Central Asia, three of which share a border with China. A wide range of Eurasian security issues, from the protection of infrastructure to the fight against organized crime, have topped the OSCE’s agenda recently.

The Emerging EU-OSCE-China Security Nexus

The OSCE and China will not be meeting for the first time in Berlin. A decade ago, the organization engaged Beijing in tentative talks on China becoming an OSCE cooperation partner in Asia. And over the past 20 years, EU and US security experts have attempted to convince Beijing to embrace the OSCE as a blueprint for East Asia’s security architecture. None of these initiatives yielded any results.

Now, as Beijing continues to promote its “One Belt, One Road” initiative to build an infrastructure and transportation corridor from Asia to Europe, it is in a fundamentally different context that the OSCE and China encounter each other in the German capital.

China’s projects in Central Asia are increasingly confronted with the same security concerns as Chinese economic entanglements in other unstable regions. Beijing is under growing pressure to protect Chinese assets and citizens abroad in the face of civil unrest, terrorism, and anti-Chinese sentiment over environmental and labor issues. China’s steadily growing dependence on energy imports from Central Asia, combined with the fear of transnational terrorism and refugee flows, has also heightened Beijing’s interest in stabilizing Central Asia and neighboring countries, notably Afghanistan.

Like China, EU member states also have significant stakes in the energy infrastructure of Central Asia. Moreover, the recent mass influx of migrants into the EU and the terrorist attacks in Paris and Brussels served as forceful reminders of the need to remain actively engaged in stabilizing Europe’s wider neighborhood.

EU and Chinese security interests do not just converge in Central Asia, however. There is substantial disagreement between the EU and China over how security should be achieved in the region, with differences being particularly pronounced when it comes to the role of human rights, the rule of law, and the sustainability of infrastructure.

EU Deployment of the OSCE

In light of these differences, the OSCE is an attractive tool for pursuing EU member states’ security interests in Central Asia vis-à-vis – and on occasion together with – China.

First, EU member states have already invested considerable resources into the OSCE’s efforts to get security in Central Asia right, for example by building capacities for good governance, border management, and combatting illicit trafficking. These capacities should be deployed when responding to Chinese security activities in the region.

Second, EU member states’ engagement with China within the framework of the OSCE, renowned for its “stealth diplomacy,” would attract much less public attention than similar engagement on a bilateral or EU level, opening up room for a frank exchange with Beijing.

Third, the OSCE’s holistic notion of security — encompassing politico-military, economic, environmental, and human aspects — provides a suitable “playing field” for addressing a wide range of issues in a cross-dimensional manner.

Finally, given the challenging behavior of Russia and the Central Asian republics within the OSCE, EU diplomats serving with the organization have extensive experience when it comes to promoting and upholding a security paradigm derived from the liberal norms of Western democracies in the face of competing authoritarian notions of governance.

To convince Beijing of the value of engaging more actively with the OSCE, EU member states should suggest areas of cooperation that would be of obvious and genuine interest to China. At the same time, they should focus on areas that will also have the support of the US and Canada, the EU’s most important partners within the OSCE. Proposed projects should have at least the tacit consent of other OSCE states, each of whom holds the power to veto initiatives.

With these considerations in mind, the EU should start deploying the OSCE strategically to engage China in all key areas of common concern: the protection of critical infrastructure as well as the fight against organized crime and terrorism.

Points of Departure for Engaging Beijing

Seizing the momentum that might emerge from the Berlin connectivity conference, EU member states should promote greater Chinese participation in OSCE expert workshops. In particular, Chinese officials should be invited to join training courses for Central Asian law enforcement officials on the protection of energy infrastructure from cyber-attacks. Further confidence-building measures in this field could eventually lead to a wider dialogue on cyber security.

With a view to combating the illicit trafficking of arms, drugs, and human beings, Chinese experts should be encouraged to participate in seminars at OSCE field offices, for instance at the organization’s Border Management Staff College in Dushanbe. OSCE training events on drug trafficking for Afghan police officers could be another venue open to Chinese participation.

Even though the EU and China clearly have a joint interest in combating transnational terrorism in Central Asia, the OSCE is not the right forum for a strategic dialogue on counter-terrorism or the exchange of sensitive information. What the OSCE can do is help the EU engage China in a dialogue on the root causes of violent extremism and terrorism.

EU member states should encourage the OSCE to invite Beijing to take part in select events of its campaign against violent extremism, which is intended to raise awareness in participating states and partner countries. Engaging China in a dialogue on countering radicalization within the OSCE framework could open up a venue for addressing wider human rights and rule-of-law issues, which have so far been stumbling blocks in EU-China cooperation in the fight against international terrorism.

As the EU and its allies grapple with China’s expanding global security activities, creating a new space for engagement with Beijing can be a useful tool for building trust and increasing global security. Yet European policymakers should proceed with caution and refrain from overreaching.

Entering into security cooperation agreements should not be seen as an end in itself. Engagement with China in Central Asia through the OSCE has to have realistic, substantive, and measurable goals. Above all it needs to help further the EU’s own security interests.