Emmanuel Macron’s election as president of France was greeted with a collective sigh of relief throughout Europe – surely the populists had reached the limits of their nihilistic appeal, and now the idealists (transatlanticists? Europhiles?) would have a chance to reclaim ground. But if Macron’s victory restored Europe’s engine, who’s steering the car?

Fortunately, the tune-up comes at a time when the Germans are ready to take the wheel. According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in spring of 2016, a majority of Germans felt that their country should “help other countries deal with their problems” (while majorities in every other European country outside of Spain and Sweden wanted to focus on their own issues), and 62 percent acknowledged that their country played a more important role than it did ten years ago. And these confident Germans want to bring the rest of Europe along for the ride: two-thirds of Germans said their country should take allies’ interests into account even if it meant making compromises, and three-quarters said the EU should play a more active role in world affairs.

When it comes to priorities, there are several issues the Germans would like to tackle. Over 90 percent said that climate change posed a serious threat to Germany (a result echoed by a Forsa survey conducted in mid-June this year by our sister publication Internationale Politik, more of which below). Germans were less concerned by the rise of China, tensions with Russia, and the prospect of global financial instability, with only 28, 31, and 39 percent, respectively, describing these as “major” threats to Germany, while 85 percent were worried about the Islamic State – well before the December 2016 terrorist attack in Berlin.

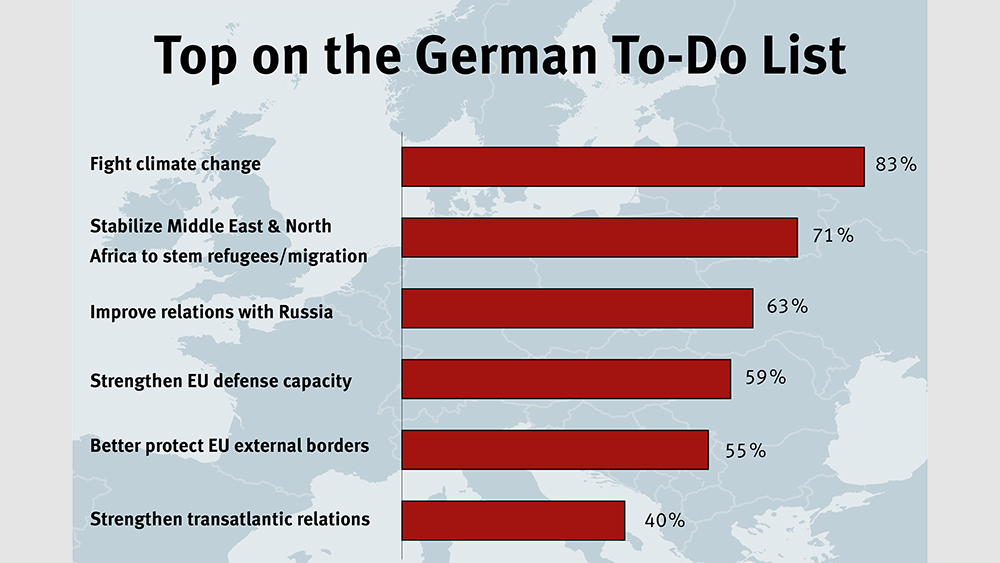

Still, few Germans want to address challenges of this kind with stronger security measures: A third wanted to increase spending on national defense, compared to half who wanted to keep it at current levels and 17 percent who wanted defense spending to decrease. Two-thirds said that “relying too much on military force to defeat terrorism creates hatred that leads to more terrorism.” The recent Forsa-IP survey found higher support for more robust measures: 59 percent wanted to strengthen EU defense capabilities, and 55 percent thought it was important to strengthen the EU’s external borders. But many more Germans (71 percent) were interested in combating the causes of refugee flows by working to stabilize states in the Middle East and Africa.

While fixing the strained relationship with Russia is not among the Germans’ top priorities, economic ties are seen as important. In the Pew survey, 58 percent of respondents expressed interest in strengthening their country’s economic relationship with Russia. Only 35 percent opted for being tough on foreign policy disputes.

Lowest on the Germans’ foreign policy priority list is improving transatlantic relations: only 40 percent described it as important. Among East Germans, this ranked even lower: only 29 percent of East Germans think strengthening the transatlantic relationship should be a priority.

In fact, Germans may be willing to look further abroad for future partners: According to Pew, Germans were split down the middle when asked to decide whether the United States or the “countries of Asia” would be more important to Europe in the future.