As chancellor, Angela Merkel has done little to build a roster of politicians who might succeed her – in fact, one of the strengths has been her ability to quash potential rivals. Nevertheless, as she prepares for her fourth term of office, some names have started emerging.

Long before she became chancellor, Angela Merkel thought about how important it was for a politician to know when it was time to leave politics. This was in 1998, and Merkel had just witnessed how Helmut Kohl’s electoral defeat put an ignominious end to his 16-year chancellorship. She reasoned that she never wanted to leave politics as a lame duck herself. Ever since, she has considered an exit on her own terms the ideal end to a successful political career.

The chancellor’s hesitation to confirm her candidacy in the fall of last year was likely connected to that hope. She was aware of the fact that every missed chance to determine the end of her career herself reduces the chances that she will be able to at all. At the same time, given Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, and Brexit, there has hardly been a worse time for the most experienced and powerful European head of state to leave the stage.

Politicians who intend to stay in office as long as they are able have no need to consider their succession, but one who would determine her own exit must. Yet since her surprising rise to the top of the CDU in the year 2000, Merkel has been too busy warding off her intra-party challengers to pay any attention to who might come after her. Early on, she surrounded herself with a close circle of trusted advisers – Peter Altmaier, Ronald Pofalla, Hermann Gröhe – but these were sworn to unconditionally defend Merkel’s chancellorship rather than advance their own prospects. It may be a coincidence, but the chancellor removed the only person who showed the ambition and talent to one day inherit her position – Norbert Röttgen – in 2012. No wonder that in 2017, no one at the top of the CDU or within the administration presents him- or herself as an obvious alternative.

Angela Merkel has announced that she will run once more this fall for a full legislative period. Assuming she is successful, that leaves her four years to establish a successor. Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble would have been an obvious choice during the refugee crisis. In the turbulent period at the end of 2015 and the beginning of 2016, he might have seemed like an anchor of stability if Merkel had fallen over her controversial management of the situation. But if she has the chance to hand over power on her own terms in four years, Schäuble will be nearly eighty, too old for serious consideration.

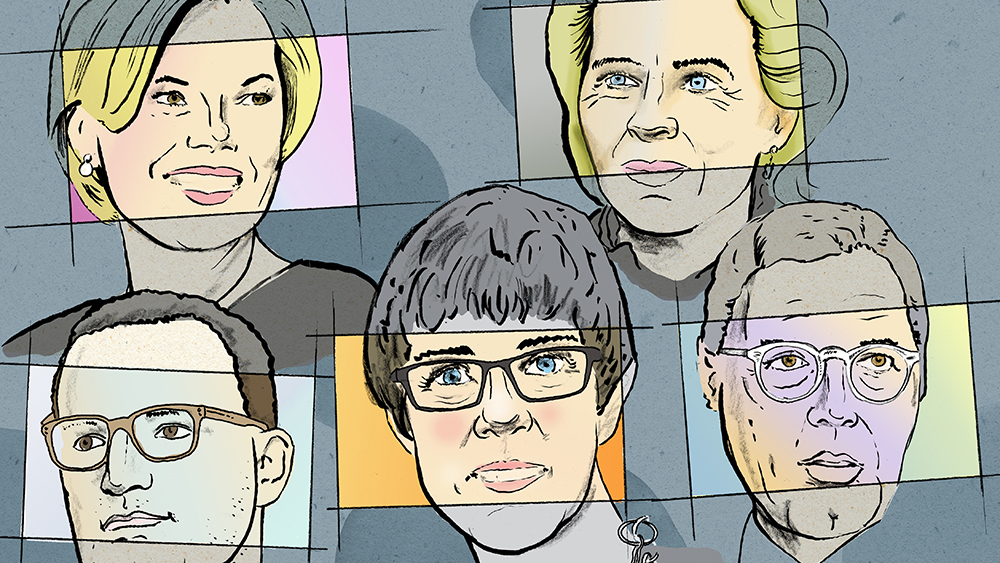

The Merkel Generation

The situation is somewhat different with the second name that has cropped up in recent years: Ursula von der Leyen. The 59-year-old has gone out of her way to play down any ambitions of her own. She has said that “a generation only needs one chancellor,” making it clear that in her case, it is Angela Merkel. Nevertheless, Berlin politicians and observers are firmly convinced that not only, von der Leyen can easily imagine herself as Merkel’s successor, but that she also believes herself to already have the skills necessary for the top job.

A doctor by training, von der Leyen made her first appearance in national politics in 2004. Since then, she has headed three federal offices: the ministry for women and family and the ministry for labor and social affairs in addition to her current post at defense. Her foreign policy credentials may also put her ahead of the competition. During the refugee crisis, von der Leyen was one of Merkel’s most visible and loyal defenders – and yet she is also one of the very few CDU politicians who have openly fought with the chancellor, and done so as an equal.

Clearly, von der Leyen is different from the chancellor. She is a politician who is willing to eloquently and forcefully pursue her projects. But this trait has not only helped her become one of Germany’s most visible political actors; it has also hurt her in the CDU. Like Merkel, she is a modernizer. But where Merkel mostly declines to spell out her plans, implementing them either bit by bit or in sudden bursts, von der Leyen represents her positions openly and is happy to engage in public debate. This has led the party to direct its criticism of her efforts to modernize the military, for example, toward von der Leyen rather than the chancellor herself. This is one reason for the obvious distance between the defense minister and her party, and a possible obstacle to any future in the chancellery.

Respected, Not Revered

Within her party, Merkel is one of the most respected politicians. But unlike Helmut Kohl, she is hardly a revered leader. For twelve years now, she has guaranteed that the party remained in power, but she did so by pragmatically incorporating the shifts of a changing society rather than directing them according to the preferences of the Christian Democrats. Merkel’s twelve years in office have thus been accompanied by a certain lack of enthusiasm from her own party, which cannot escape the feeling that it has traded its values for power. This poses a challenge as well as an opportunity for her successor: any aspiring candidate who promises to pay more heed to the party’s vision should have a fairly low bar to clear.

The CDU politician currently pursuing this strategy most avidly is Jens Spahn. This ambitious young politician has become a beacon of hope to those who want the CDU to return to its conservative, fiscally liberal profile. Spahn is only 37 but has already been in the Bundestag for 15 years. He is highly driven: already in 2013, after the last national election, he saw himself as destined for a position in the cabinet. When he did not get it, he fought a very public battle for a place on the CDU executive committee, the party’s most powerful body. Schäuble himself took him under his wing as his “parliamentary state secretary” at the finance ministry. While this is not a particularly important office in government, Spahn has nevertheless become one of the most well-known and influential CDU politicians. In a party that avoids public debate, he will publicly contradict Merkel and turn such attacks into his personal brand. For some time now, he has been on the rather short list of politicians credited with the clout to succeed her.

Similar to Spahn, Julia Klöckner set herself apart from Merkel during the 2015–16 refugee crisis. Ever since, she has made discomfort with Islam into her theme. Had she won the 2016 state election in Rheinland-Pfalz, she would be the favorite to succeed Merkel today. She did not win, but she still isn’t out of the running. As deputy party head, Klöckner has given the CDU a youthful, friendly face. She also offers something to the long-disappointed Christian Democrats who are interested in tradition and homeland without playing exclusively to the party’s conservative wing or indulging in the bitterness that sometimes characterizes Spahn. She is just as ambitious, but manages to conceal her aspirations with a certain winning charm. For a party that experienced the Kohl-Merkel transition as a loss of political orientation, she represents an emotional homecoming.

Still, Klöckner has headed neither a federal ministry nor a state government. She is seen as inexperienced and cannot rely on charisma alone to sweep her into the chancellor’s office. If Merkel were to offer her a cabinet post in the future, she’d become one of the most promising candidates.

A Dark Horse

Given the current office holder, it is fitting that the politician with the best chance of succeeding is not the ever-present Ursula von der Leyen, the ultra-ambitious Jens Spahn, or the happy warrior Julia Klöckner. Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer may be a dark horse, but she resembles the current chancellor the closest. Like Merkel, she is an unpretentious, pragmatic, technocrat who does not give the appearance of using politics as a stage to realize her personal ambitions. And that is not the only reason why the minister president of the tiny state of Saarland actually stands a chance of becoming the next chancellor: she is one of Merkel’s most unquestioningly loyal followers, has pursued Merkel’s modernization plans, and supported the chancellor unequivocally during the refugee crisis. She has also proven her ability to exercise power: in Saarland, against the chancellor’s wishes, she broke up the CDU, Green, and FDP coalition, saying that the FDP was not sufficiently serious to be a real partner. Unlike Spahn, who is inclined toward economic liberalism, Kramp-Karrenbauer stands for a CDU anchored in the social welfare economy. She won the most recent election in her state by an unexpectedly wide margin. This was the beginning of a series of disappointments for Martin Schulz, who was to be the SPD’s savior in September’s federal elections.

For each of the potential successors, it would be extremely helpful if the chancellor gave them the chance to build a stronger profile in office – allowing them to take the reins a year before the next election, for example. But Merkel has made it clear that she wants to fulfill another full four-year term if she is re-elected later tnis month. So there will likely be a piecemeal shift in power rather than a single dramatic change. Kramp-Karrenbauer, for example, could take over the job of party chief in the middle of the legislative period which would give her a strong claim to the top job when the next campaign season begins.

Merkel, however, has always believed that her predecessor Gerhard Schröder made a serious mistake when he gave up the office of SPD chief during his chancellorship as this was seen as a clear sign of political defeat. Merkel will not make the same error; she will likely hand over the reins of the party only as a signal of an upcoming transition, and only when she is ready. It would be the first step in the final farewell that she has contemplated for two decades.

But Merkel also knows that in politics, little goes according to plan. Few chancellors have managed to determine their own exit, and the plans of those who would become chancellor in their place are rarely more successful. It was the same after Kohl was voted out, when many in the CDU hoped their own fortunes would rise, only to see their ambitions dashed. In the end, it was Merkel who rose to power, someone no one had on their radar in 1998. And who knows – history could repeat itself.