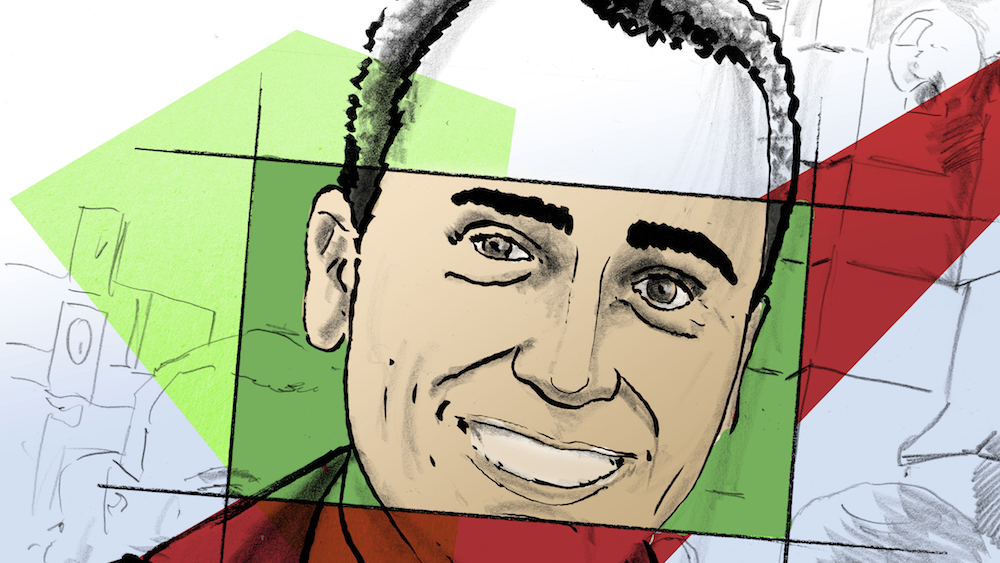

Under its youthful leader, the populist Five Star Movement has shot to the top of polls in Italy. But does the popular 31-year old, considered a lightweight by critics, have enough political punch to win power in the coming parliamentary elections?

To outside observers, Luigi Di Maio, the immaculately groomed 31-year-old hoping to become Italy’s next prime minister, is as ambiguous as the Five Star Movement (M5S) he leads. Described as poised and reassuring, he is the antithesis of the rabble of rebels initially brought together by Beppe Grillo, the messy-haired, loud-mouthed comedian who founded the opposition movement in 2009 against a backdrop of economic decline and severe discontent with the traditional political class.

Yet ever since he was elected the youngest-ever deputy speaker of Italy’s lower house of parliament in 2013, Di Maio has shown signs of being as temperamental as 69-year-old Grillo, and equally prone to gaffes. An attempt last year to compare former prime minister Matteo Renzi to Augusto Pinochet fell flat after he referred to the late Chilean dictator as Venezuelan; in November he described Russia as “a Mediterranean country.” He has also made several linguistic and grammatical errors in his native Italian.

Blunders aside, in 2016 he was ranked among the most influential people in Europe under the age of 30 by Forbes magazine, and in September he became leader of the M5S after winning an online ballot. The party’s founder Grillo has always excluded running for office because of a 1980 manslaughter conviction after a car crash in which three people were killed. So with Renzi forced to quit after a botched referendum on constitutional reform in December 2016 and the ruling center-left Democratic Party in disarray, Di Maio can now position himself as a serious contender in the electoral race.

He was just 21 when he was brought along by a friend to participate in Grillo’s debut “V-Day” protest against corrupt politics, with the “V” standing for vaffanculo, the Italian word for “fuck off.” Di Maio was tasked with collecting signatures for a petition calling for politicians with criminal records to be banned from standing for parliament.

But it has been his ability to distance himself from the party’s bombastic, conspiracy-theorist, euroskeptic tone that has not only aided his meteoric rise but also broadened the party’s appeal to such an extent that it is now Italy’s most popular. Di Maio has pledged to “rescue” Italy, a country with a perennially sluggish economy, high unemployment, and huge public debt, not to mention a vast number of migrants who have arrived on its shores in recent years. Still, as he travels around the country garnering support ahead of general elections on March 4, he is facing the double challenge of disproving critics and convincing a weary electorate to place their faith in a party that has yet to be tested at the national level.

“There are those who continue to say that we are anti-politics,” Di Maio told me in an email. “But the reality is we are another type of politics. It’s their way of discrediting us, but if Italy is at the point it is today, the responsibility is certainly not ours.”

From Engineering to Politics

Born in Avellino, a town close to Naples in the southern Campania region, di Maio’s penchant for order emerged early, when he decided he wanted to become a policeman at the age of 10. That aspiration was influenced by his upbringing in a region ravaged by the Camorra mafia organization.

While his inclination towards activism might have been shaped by his father Antonio, a former construction firm owner who was involved in the now-defunct neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI), their political views differed. Earlier this month Di Maio reiterated his party’s condemnation of fascist ideology after being criticized for not taking part in an anti-fascism protest in the northern town of Como.

The eldest of three siblings, Di Maio studied engineering at Naples University before switching to law, but never completed either course. He said he became civically and politically engaged while at high school and university, where he helped establish a students’ union. Di Maio’s work experience includes waiting tables and laboring on building sites, as well as a stint as a steward at a Naples football club. As a student, he co-founded a web and social media marketing firm, and in 2012 created a documentary about the demise of small businesses in Naples.

A car lover, Di Maio has said his entrepreneurial idol is Enzo Ferrari, the racing driver and founder of the iconic sports car company. Meanwhile, in the world of politics, he told Vanity Fair earlier this year that he looks up to Alessandro Pertini, a socialist politician who was Italy’s president from 1978 until 1985. Yet he himself generally represents the conservative side of the M5S.

Di Maio recently split from long-term girlfriend Silvia Virgulti, a party spin-doctor credited with nurturing his communication skills and boosting his image. “They say the love story is over but I think she’s still his adviser,” said Alberto Castelvecchio, a public speaking professor at Rome’s Luiss University. “He listens to his spin-doctors – he’s very disciplined and studies hard, and he respects what they suggest.”

Nonetheless, it’s when he speaks publicly that the inconsistencies surface, Castelvecchio added. “You can see the difference between the two Di Maios: one is the perfectly programmed storyteller, and the other – who comes out when he has to improvise – is the real Di Maio, who unfortunately is not as brilliant as his spin-doctor.”

His boyish, clean-cut look and moderate manner have helped the party gain a lead over its rivals in opinion polls since September, with an Ipsos survey on December 18 positioning M5S at 29.1 percent, ahead of the ruling Democratic Party’s 24.4 percent. “He looks perfectly designed to be the grandson every grandmother would like,” Castelvecchio added.

The Populist Challenge?

Di Maio’s skyrocketing popularity comes despite outcries over how badly M5S politicians have run Rome and the northern industrial city of Turin, a lackluster performance in local elections in June, and a defeat in Sicily’s regional elections in early November. And as things currently stand, there is little chance of the party winning the 40 percent of the vote required to govern alone. A new electoral law was recently introduced allowing parties to form coalitions ahead of an election – something the M5S has vehemently opposed.

That is, until now: in a sign of his ability to change tack, Di Maio told an Italian radio station on December 18 that if it fails to reach a majority on election day, M5S might appeal to parties that have won parliamentary seats to forge an alliance. Until then, a key test will be his ability to unite a group made up of militants from across the political spectrum while giving voters a clear impression of what the party represents.

Ever since the Brexit vote, the party has softened its stance towards Europe, saying a referendum on the euro would be a “last resort.” But it has become tougher on immigration, an issue that will dominate the campaign. The party’s views on the topic now appear to be more in line with the far-right Northern League, even though in 2011 Di Maio volunteered to help asylum-seekers in Naples settle in, according to his online CV. And even with the shift, M5S’ core values of free water, sustainable transport, sustainable development, free internet access, and environmentalism remain mostly intact.

If it manages to seize power, the party has said it will place ministerial posts in the steady hands of people with high institutional profiles – magistrates, economists, professors, and the like. But competence is not something that seems to bother those supporters drawn to the radical ideals that helped establish the party, and which are expected to help it emerge as a clear winner, at least in terms of vote percentage.

“It’s about revenge, not competence,” said Castelvecchio. “They are bitter about the kind of climate we have in Italy… and they want to send the cronies home.” Meanwhile Di Maio says he never set out to become a politician, and even now he is not dwelling much on the prospect of leading the country. “I’m committed to bringing forward a program, an idea, values… after which it will be up to citizens to choose which way to go.”