As our author completes the overland part of his long journey, he reflects on what he has learned about the hype and the reality of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

After travelling 21,400 kilometers overland, I finally reached the New Silk Road’s birthplace in Kazakhstan. Nur-Sultan is a strange city—a young and isolated metropolis trying its best with its glass skyscrapers and yurt-shaped megamalls to impose a shiny sci-fi futurity on the primordial Kazakh steppe. It was founded 21 years ago as “Astana”—literally “capital city,” a new capital for a newly independent nation, but in 2019 it was renamed in honor of Nursultan Nazarbayev after he resigned as president. Kassym-Jomart Tokayev is Kazakhstan’s new head of state, but Nazarbayev is “Leader of the Nation” and chairman of the Security Council. Having held the office of president since the country’s creation in 1990 amid the break-up of the Soviet Union, the 79-year-old still dominates Kazakhstan’s political scene.

It’s late November, and the temperature is 30 degrees below freezing. Locals tell me that winter hasn’t truly arrived yet, and that it will reach minus 40 or 50 before January. Walking the vast boulevards between citizen-humbling monuments, my eyelashes start freezing together and ice crystals form in my nostrils.

Nur-Sultan is a hard place. The former capital, Almaty, with its beautiful mountains, cafe culture, and temperate Southern climate is a nicer city, but Nur-Sultan is a more poignant symbol of 21st-century Kazakhstan.

The city blends Kazakhstan’s mythologized nomadic past with the cold gleam of oil money. Alone on the harsh steppe, it embodies the country’s future-facing hopes and mad ambition. Kazakhstan is troubled, and like the rest of Central Asia, it lives with the seemingly incurable plagues of corruption and debilitating bureaucracy. At the same time, it has potential and vision, boasting oil-and-gas-funded urban development, strong human capital, and striking visions like the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy—an ambitious plan to jump into the world’s top 30 economies within the next 30 years.

The Birthplace of China’s Vision

Nur-Sultan is thus a fitting birthplace for an equally ambitious Chinese vision. In September 2013, behind a lectern at Nazarbayev University, China’s newly enthroned President Xi Jinping proposed building a “Silk Road Economic Belt” across Eurasia—one half of what would become known in English as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

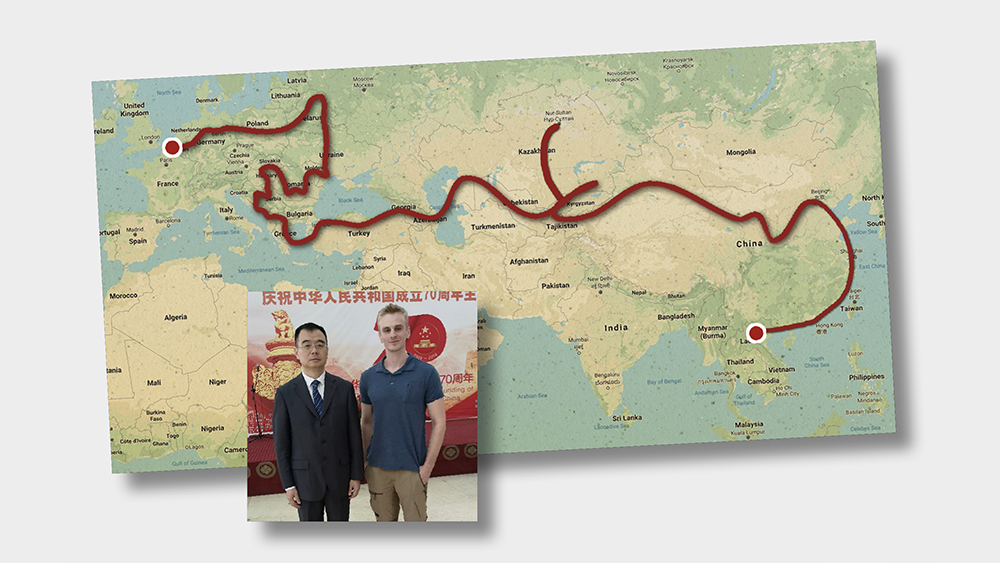

Since March 2019, I’ve been travelling this Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), or “New Silk Road.” From Brussels to Beijing, I’ve passed through 23 countries, visiting infrastructure projects, talking to experts, and trying to get a feel for how locals see Beijing-sponsored development.

As I proposed in my inaugural article for the Berlin Policy Journal, the BRI is something of a blank canvas onto which commentators and decision makers can project their desires and assumptions. The policy documents behind the initiative do absolutely nothing to narrow the scope of the BRI, imbuing it with the potential to describe pretty much any aspect of human endeavor anywhere. The Chinese literature associated with the BRI paints it as a highly idealistic foreign policy concept, while knowledge of Chinese political processes casts it in the role of a campaign slogan, designed to mobilize support in a certain direction while leaving details to be filled in further down the chain of command.

An Undefined, All-Encompassing Idea

Most people I speak to about the SREB conceptualize the initiative as a physical route running from East to West. Beijing is keen to promote the physical dimension of the SREB, but it is not alone in doing so—almost every single country I’ve visited has marketed itself to me as a “transit” or “logistics hub” for East-West trade. In countries like Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, where oil and gas still provide a worryingly large percentage of GDP, embracing a more logistics-based economy is an important step toward economic diversification. In many “BRI countries,” governments and observers take it upon themselves to brand projects as part of the “Belt and Road.” Even those with no Chinese involvement, such as the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway, are associated with China by simple virtue of providing East-West connective infrastructure.

Building a route across the Eurasian landmass is a powerful, yet simple idea. In planning my exploration of the SREB as an overland journey East, I myself have been engaging with this narrative, drawn by its easy appeal. Undefined and all-encompassing, the BRI is pretty much what you make of it. If it means East-West overland trade infrastructure to you, then that’s what it means. But if you are looking at the larger picture of what Beijing has been funding in Eurasia, or what has been tagged “BRI,” then East-West trade is not nearly the full story.

My journey from Brussels to Beijing has revealed a rag tag combination of Chinese direct investment and credit that is highly specific to country and regional context. In financial terms, coal plants are more important than roads, and just as the “Silk Road” itself was in fact a collection of multiple merchant-led routes, Beijing-financed transport infrastructure is often locally conceived and has little to do with overarching East-West corridors.

A Tendency Toward Experimentation

It’s certainly not a straight line from Beijing to Brussels. The “China-Railway Express” is a much-celebrated element of the BRI brand, producing endless “new” connections between European and Chinese cities. Its pre-2013 growth, led by private needs for a cheaper Central China-Central Europe route, is an interesting story, but the truth is that Europe-China rail freight will only ever be a drop in the ocean of global trade. The promise of transit revenue on Europe-China traffic is appealing to countries stuck in the middle of the continent, but a more overlooked story is the role new infrastructure might play in stronger inter-regional connections.

The elements of the BRI that appeal most to commentators are grand geo-economic ideas, like connecting the COSCO-owned Piraeus port in Greece with markets via the Beijing-sponsored Budapest-Belgrade railway. But these plans are trumpeted more by academics than practitioners, and the conversations I’ve had throughout my journey have left me with the impression that these ideas, which may be appealing on a macroeconomic level, are rarely followed through in practice.

This is not so much a failure on China’s part—it is more likely a reflection of tendencies toward experimentation and a demonstration of Chinese enthusiasm for signing lots of non-binding memoranda of understanding (MoUs). Chinese officials seem to throw lots at the wall and see what sticks—sometimes locals and the international press misinterpret apparent enthusiasm for serious commitment. At most, supposedly global-trade-reshaping routes like the Middle Corridor through the Caucasus are about building a little extra redundancy into China’s trade networks.

Associations with the Past

Along with the appealing cross-continental dimension, the BRI’s romantic connection with the ancient Silk Road also offers a temptingly cyclical reading of history. At Nazarbayev University, on September 6, 2013, Xi Jinping said wistfully: “Today, as I stand here and look back at that episode of history, I can almost hear the camel bells echoing in the mountains and see the wisp of smoke rising from the desert.”

This association with the past promises revitalization to left-behind continental economies, but also has a wider appeal. People like stories about renewal, and as the emergent 21st century superpower, anything China does taps into a universal thirst for novelty. Of course, the BRI itself is a new concept for a collection of policies that are far less new. China started building and funding infrastructure long ago, especially in Africa, and many of the most recognizable BRI projects have pre-2013 origins. Every element of the BRI taken on its own predates 2013. It is their collective articulation as a foreign policy concept and brand that is new—it is in a sense the practice of putting a name to Chinese economic power.

The BRI dovetails with wider interest in the “China rise” narrative, and because a powerful China is a novel concept in modern geopolitical terms, the BRI automatically becomes an alternative for those dissatisfied with the status quo. In the Western Balkans for example, Beijing is a fairly recent geopolitical player. It arrives with little historical baggage and ready to serve as a foil to EU partners with whom countries in the region are increasingly disillusioned. In worldwide terms, the BRI represents a Chinese development model that contrasts with paternalistic Western approaches to aid that are perceived as having failed developing countries.

Popular Unease

But not everyone is happy with the BRI and with increasing Chinese economic presence. In Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, the fact that Beijing is a neighbor and familiar face in the history books works to Beijing’s disadvantage. China’s levels of popularity are incredibly varied worldwide. Beijing is able to muster large support for diplomatic maneuvers, but the respect it is shown by other governments does not always reflect public opinion in those countries. Among China’s Central Asian neighbors, friendly government-to-government relations mask widespread Sinophobic feelings.

The same is true of another neighbor to China—Vietnam, where colonial domination from the North occupies a thousand year stretch in the history books. As in Central Asia, the past provides motive (or pretext) for widespread Sinophobia.

Vietnam is where my overland travels end and the “Maritime Silk Road” begins that connects China to Southeast Asian ports and by sea to East Africa and Europe beyond. From Nur-Sultan, I have travelled another 8,300 kilometers and crossed China. The last 2,300 kilometers from Beijing to Nanning in Southern China are covered by high speed train in 11 hours. From Nanning, I followed the well-worn tourist trail into Vietnam, queuing at the border with dozens of Chinese tourists heading south for a cheap holiday.

My journey, however, continues, and along the Maritime Silk Road my next stop beckons: Singapore.