The United Kingdom has been accused recently of stepping off the international stage, leaving Germany and France to run the show. The notion of British retreat, however, needs a more nuanced assessment.

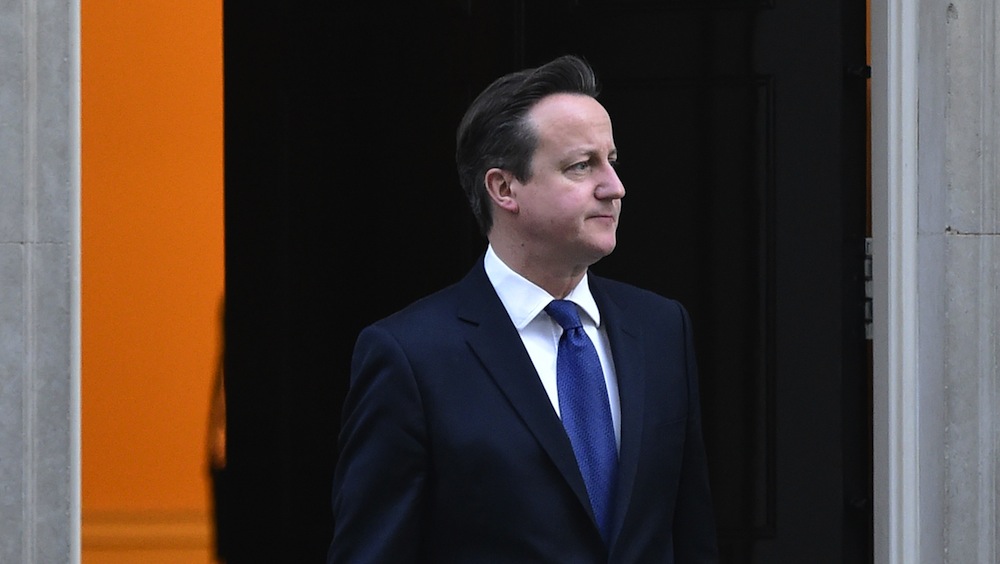

It used to be common to speak of Europe’s “Big Three” – Germany, France, and the United Kingdom – but in the negotiations with Russia over the future of Ukraine the UK has been seemingly absent. Not only has the British government taken a backseat in the management of the crisis, leaving German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the steering wheel, but, while Merkel and French President François Hollande locked horns with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Minsk in early February 2015 as the crisis appeared to be spiraling out of control, Prime Minister David Cameron was nowhere to be seen. Where are the Brits?This apparent disengagement by Britain is part of a broader set of actions that have given rise to a bout of national soul-searching about the country’s future role in the world while raising questions in European capitals and Washington about whether Britain can still be counted as one of the world’s major powers.

For example, can Britain help Europe craft effective responses to challenges in its neighborhood so long as Prime Minister David Cameron promises the country an in-out referendum on its EU membership should the Conservatives win the general election on May 7? The government also seems relaxed about allowing national defense spending to fall below 2 percent of GDP six months after hosting a NATO summit at which it pledged – along with other members of the alliance – to uphold this threshold. And, as the recent report by the British House of Commons Defense Committee noted, British troops are now largely absent in Iraq as other Western countries help the Iraqi government battle the Islamic State. What happened to Britain rejecting the notion of “strategic shrinkage,” as former Foreign Secretary William Hague put it at the beginning of the coalition government?

Rebuilding Foundations

While these are fair questions, Britain’s seeming lack of engagement in the Ukraine crisis does not paint an accurate picture of the country’s overall foreign policy. First, the government’s core priority is to rebuild the foundation of the UK’s long-term economic prosperity. The financial crisis of 2007-08 exposed the bankruptcy of a British economic model that was overly reliant on private debt, public sector spending, and tax income from a financial sector on steroids.

As a result, the government has been willing to let certain key defense capabilities lapse, including essential assets such as maritime patrol aircraft, in the belief that it will be able to reinvest in the country’s military power capabilities later. Instead, the government has prioritized what it terms “commercial diplomacy,” leveraging Britain’s diplomatic connections and historic links to generate trade with and investment from emerging markets.

Second, British public opinion is suffering more than most from intervention fatigue following the country’s expensive and bloody interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq. In August 2013 the government lost a parliamentary vote on military intervention in Syria and changed its policy, a climb down clearly attributable to the government’s unwillingness to take on a public estimated to be 70 percent opposed to any such intervention. The government must also manage a far more complex domestic political environment. A historic fragmentation of the British party system is currently underway, with the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and the Scottish Nationalists likely to play an important role in the outcome of the upcoming election, making the government far more risk-averse than in the past.

Third, the fact is that all governments inhabit a world in which the exercise of national power to achieve external goals is exceedingly difficult, and all countries, Britain included, are currently more selective in where they put their effort. In this context, the British government has made some intelligent choices in the past five years. Sustaining its pledge to spend 0.7 percent of national GDP on overseas assistance allows Britain to help promote stability and growth in parts of the world that would otherwise likely become sources of regional and international instability.

Its chairmanship of the G7 in 2013 put the notion of “open government” at the vanguard of the international agenda at a time of growing public frustration with tax avoidance by multinationals and opaque, sometimes corrupt, tendering processes for major international infrastructure projects. Its campaign against sexual violence in conflicts has made it harder for governments inside and outside conflict zones to turn a blind eye to this devastating phenomenon. The government has also been right to focus on strengthening domestic and international cybersecurity. And the decision to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank as a founding member, while taken with one eye on future business and financing opportunities, also underscored the government’s desire to ensure that investment in the long-term growth of developing countries takes place within as transparent an environment as possible.

Sometimes Absence Helps

At the same time, accusations about Britain’s absence from key recent international crises do not assess whether more overt UK involvement would actually have been helpful. If Britain, one of America’s closest allies and a country with poor bilateral relations with Moscow, had demanded a leadership role alongside Merkel in the Minsk negotiations with Putin, this would probably have made agreement more difficult to achieve. Instead, the German government has been able to rely on full British support in developing a tough line on EU sanctions against Russia, including UK acceptance of the impact on the City of London’s role as a base for Russian corporate financing. In a similar vein, overt interference by the British government, as the former colonial power, in support of the “Occupy Central” protesters in Hong Kong in 2014 would probably have made it harder for the various parties to arrive at a peaceful solution.

The notion of British retreat from the world stage needs a more dispassionate assessment. Britain still has the world’s fifth-highest defense budget, the sixth-largest economy, one of its two leading financial centers, and is the second-largest contributor of international financial assistance. It remains one of five permanent members of the UN Security Council and a nuclear power. Not bad for a country representing under one percent of the world’s population. British diplomatic influence is enhanced by its membership in some of the world’s key institutions, from the EU, NATO, and G7 to the G20 and the Commonwealth. And Britain’s capacity to coalesce solutions benefits from the use of English as a global lingua franca, by London’s status as a global hub, and the reach and influence of its media, universities, and non-governmental organizations.

In addition, current public antipathy to British overseas military interventions could ease in the future, especially if the threat posed by the Islamic State starts to seriously undermine British domestic security. And, while Britain may not have been in the diplomatic lead on Ukraine, there is stronger British public support for sustaining sanctions than in many other EU member states, as well as a strong belief that Britain should retain a wider international role. Being an ally to Merkel at this stage, therefore, may be more useful than trying to be a leader in the EU.

Great Still

There are, though, two serious worries for the future. The first is the government’s willingness to countenance a further decline in British defense spending. As a permanent member of the UN Security Council, Britain has an institutional responsibility to help sustain peace and stability across the world, over and above its self-interest as a nation heavily dependent on a stable global economy. The trajectory of defense spending means that the UK may be unable to fulfill this role for at least a period of five to ten years from 2016-17. While this might have been an acceptable trade-off in 2010, it is not in 2015, when Russian defense spending has moved in the opposite direction and reasons for it to interfere in European security have multiplied.

The second worry is that widespread ambivalence across Britain about the value of EU membership is undermining the capacity of British policymakers to offer leadership within the EU at a time of unprecedented risk and uncertainty. An energy union, a single digital market, service sector reform, and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are all essential components of future British prosperity and security, but very few British politicians are stepping forward to make this case. Instead, the sense of drift over Europe undermines the capacity of other major actors like Germany to play as strategic a role as they might like, given that UK presence and support cannot be taken for granted.

At a time when national power is more difficult to wield effectively than ever and leadership requires partnership, the British obsession with wondering whether it would be better off in or out of Europe is a dangerous self-indulgence that undermines its international influence.

Read more articles from the April 2015 issue FOR FREE in the Berlin Policy Journal App.