As European governments debate whether to allow Huawei to build critical 5G infrastructure, fears of economic retaliation by China play a major role in their thinking. While this is a legitimate concern, it would be a mistake if such concerns were allowed to dominate decision-making on strategic issues.

China certainly has serious economic weight, and its market is increasingly important to some European countries, but its real retaliatory power is often overstated. Governments across Europe tend to overlook an obvious fact: the EU single market—not China—is by far their most important source of economic growth.

Following the Chinese Call

As part of accelerated Chinese Outbound Foreign Direct Investment starting around 2012, Europe began to emerge as a preferred investment destination. A surge in Chinese companies’ activities to diversify their portfolio abroad resulted in mergers and acquisition of technology assets in the wealthiest European countries, and infrastructure investment in Europe’s periphery.

Against this backdrop, China sought to institutionalize political and economic cooperation with EU members, both bilaterally and through sub-regional formats. In the aftermath of the eurozone crisis and in the context of rising euroskeptic movements, Beijing benefited from the perception that China could offer attractive economic opportunities in the face of weak GDP growth and be an alternative to Brussels. The launch in 2013 of China’s global trade and infrastructure project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), further reinforced this perception. This has prompted European governments to sign Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with Beijing in hopes of securing economic benefits. At the same time, they made sure to avoid criticism of China for fear of losing out on such opportunities.

Now, the threat of Chinese retaliation if governments decide to exclude or limit the role of telecom equipment provider Huawei in their countries’ 5G is making countries that are more dependent on the Chinese market think twice. However, a look at the numbers shows that European nations have less reason to be afraid than one might expect.

A Narrative of Dependency

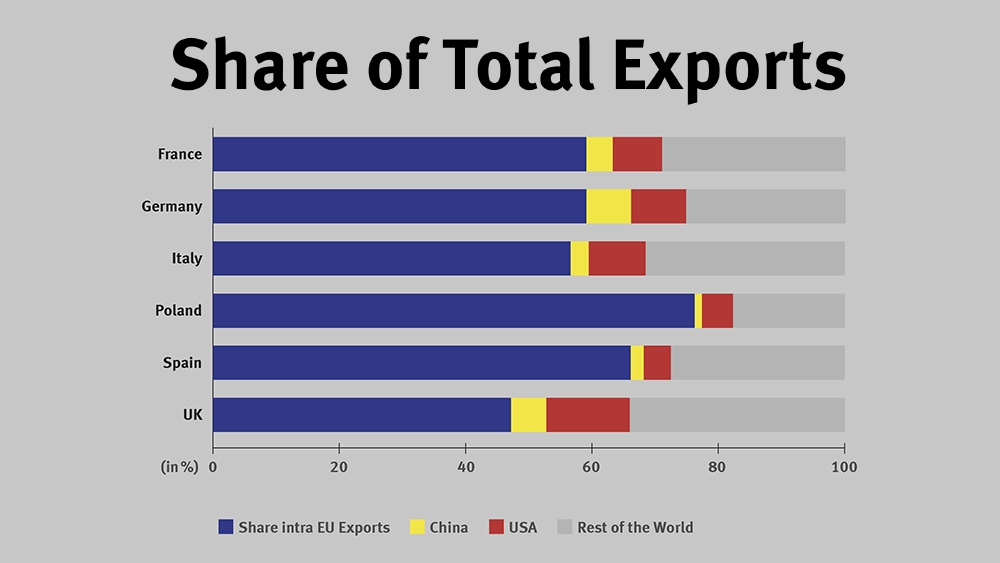

In 2018, the EU single market accounted for on average 66.1 percent total exports of the individual EU 27 members plus the United Kingdom, against an average of 2.4 percent going to China. For member states (and the UK) exports outside the single market, the share of exports to the US was on average 9.3 percentage points larger than those going to China.

These figures should help put the importance of the Chinese market for European economies in perspective and debunk the narrative that China is a source of unlimited economic opportunities. By the same token, these figures show the limits of China’s retaliatory power vis-à-vis European countries and indicate an untapped potential for the EU to leverage its economic power in relations with Beijing. In some states, the narrative about economic dependency on China is likely driven by an over-exposure of some large corporates, such as the German automotive industry, which is heavily invested in the country.

Despite this reality, the economic opportunity/retaliation argument is still disproportionately affecting how governments think about China, including on issues that have strategic and national security implications. It is possible that Chinese ambassadors’ activism across Europe is contributing to this perception.

Ambassadorial Pressure

In December 2019, Beijing’s envoy in Berlin, Ambassador Wu Ken, said that “If Germany were to make a decision that led to Huawei’s exclusion from the German market, there would be consequences. The Chinese government will not stand idly by.” Members of the Bundestag are convinced that in case of an unfavorable decision on Huawei, Beijing would go after the German car industry in China.

It turns out that Germany–which along with France has promoted itself as a leading force behind a coordinated European China policy—may be the EU member state most vulnerable to Beijing’s pressure in bilateral economic relations. In Europe, Germany has the highest share of exports to China (7.1 percent of its total exports, and 17.3 percent of its exports outside of the EU in 2018 according to Eurostat), far above the EU member state average of 2.4 percent and 7.3 percent respectively. German investment in China is also the highest in the EU. The Chinese market is particularly vital to German carmakers. Volkswagen, for example, generates almost half of its revenue in China. All together BMW, Daimler, and Volkswagen made over one-third of their car sales in the People’s Republic in 2018. In January 2019, the influential Federation of German Industries (BDI) urged companies to reduce their dependence on the Chinese market in response to China’s selective market opening and its ambitious industrial policy, which aims at reducing its reliance on foreign companies.

However, while China and the US are Germany’s single most important export markets outside the EU (7.1 percent and 8.7 percent respectively), its export markets are highly diversified, with the EU single market accounting for 59 percent of exports in 2018. So even though Germany is far more exposed than other member states to both the United States’ and China’s retaliatory power, its overall economic dependency on China is smaller than it is often made out to be, and not enough to justify an accommodating position on strategic issues.

Growing Disappointment With China

For years, European governments’ China policies were based on the premise that maintaining friendly political relations, even at the expense of standing up for their own values and interests, was key to unlocking special economic treatment in bilateral relations. Euroskeptic governments have been especially keen on showing Brussels that they had an economic alternative in China. This has made them cautious not to upset Beijing—an approach that has occasionally extended to economic policy, for example when the previous Italian government worked to water down and eventually abstained from voting on the EU investment screening framework that its predecessors in Rome had asked the European Commission to draw up.

Different European countries are now starting to be more clear-eyed about the gap between China’s promises and the trade and investment reality. For example, the Chinese market still only plays a minor role in the economy of the twelve eastern EU states that are part of the 17+1 framework for cooperation with China. They all joined the China-led format and signed BRI MoUs to cash in on Beijing’s promises for trade and investment. But on average, exports to China still only account for 1.4 percent of their total exports, and Chinese investment has continued to flow to western Europe, neglecting their region. Some of the format’s members, like Poland and the Czech Republic, have voiced their disappointment. Importantly, an average of 72.4 percent of these 12 countries’ total exports go to the EU internal market.

Italy finds itself in a similar situation. The previous euroskeptic government signed a BRI MoU with the stated goal of exporting more to China. However, Italian exports to China declined in 2019, and the Chinese market still accounts for just 2.8 percent of its total exports, compared with 56.6 percent of exports that go to the EU single market. Rome is now also taking a more realistic approach to China and has joined Berlin, Paris, and Warsaw in the push to revise EU competition policy to stand up to China and the US.

Learning from China’s Neighbors

While countries like Germany, the UK, and Finland are slightly more reliant on the Chinese market, lessons from Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan show that economic dependency does not have to translate into an accommodating position toward China.

Beijing’s East Asian neighbors depend much more strongly than European countries on China (individually, their export share to China was between 20 and 30 percent in 2018). However, they are forced to adopt a comprehensive approach that goes far beyond economic interests and factors in national security considerations, not least because of their proximity to China, which they see as a strategic rival. When Beijing weaponized its economic power against them in the past—for example over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute with Japan or over South Korea’s deployment of the THAAD missile shield—they took measures to foster economic sovereignty in response, effectively limiting China’s economic leverage instead of giving in to Chinese pressure.

European governments should learn from East Asian nations. They should put strategic considerations first and not be overly worried about China’s economic retaliation. This requires growing more comfortable with compartmentalizing the relationship into areas of cooperation and competition. In addition, while the Chinese backlash temporarily hit individual companies (e.g. South Korea’s Lotte), economic ties between China and the three East Asian nations have remained stable overall.

Indeed, another lesson from China’s immediate neighbors is that while Beijing would quickly take advantage of a Europe that was being too accommodating, it is unlikely to substantially follow through on its threats. If Europe took more measures to promote economic sovereignty, China would most likely adapt its own approach in order to continue profiting from good relations with the EU and its members instead of jeopardizing this crucial relationship.

After all, European countries shouldn’t forget that close economic ties run both ways: the EU is China’s most important trading partner. China needs the EU bloc economically and geopolitically in its competition for global leadership with the United States. As Brussels works to rebalance its economic and political relationship with Beijing, leveraging the EU’s economic power should be part of the solution.