One of the enduring narratives of 2016 was the strength of populist movements on social media. Whether Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, Front National in France, UKIP in the United Kingdom, or Donald Trump in the United States, these mostly right-wing, mostly euroskeptic politicians were believed to be particularly menacing because of their prowess on Facebook and Twitter: they seemed to have an uncanny knack for a media that mainstream parties were still grappling to understand, without much success.

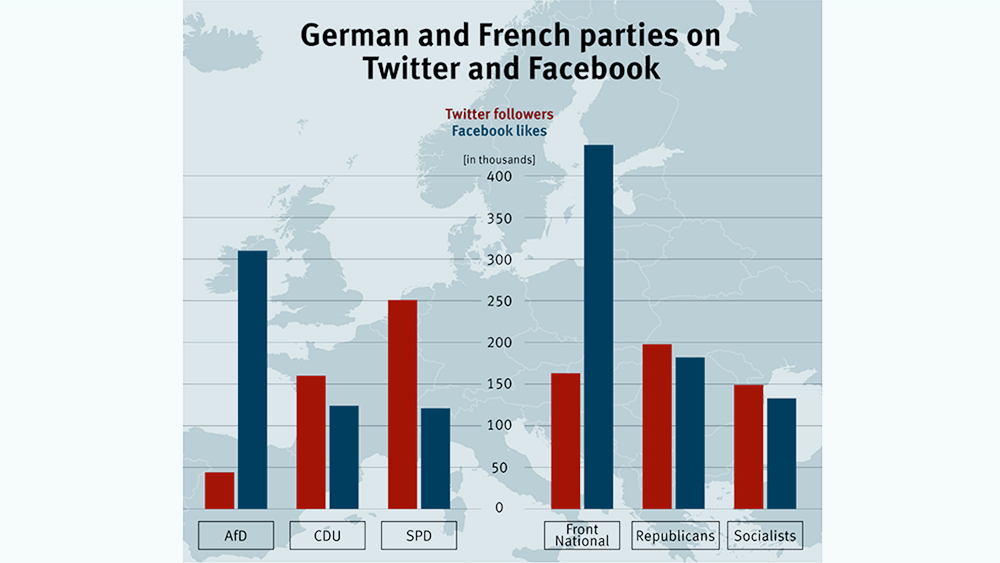

The truth is more mixed. Front National enjoys 163,000 Twitter followers, on par with France’s Republicans and Socialists, but it has a Facebook following significantly larger than the other two combined. In Germany, AfD’s roughly 44,000 Twitter followers pale in comparison to the Christian Democrats’ 160,000 and the Social Democrats’ 251,000. On Facebook, AfD roughly equals the combined weight of the other two. UKIP has about half as many followers on Twitter as the Tories and between a half and a third as many as Labor; the three each have about 500,000 likes on Facebook. And what of the Donald himself? With 18 million Twitter followers, his audience dwarfs Hillary Clinton’s 12 million, and he enjoys a similar 17 million to 10 million advantage on Facebook. But then, he was a reality TV star before he became a reality TV star and the president-elect.

But the numbers of actual followers tell only half the story. Many of these parties rely on virtual armies of automatic accounts to amplify their messages, legions of “bots” that elevate their press releases to top stories.

The Computational Propaganda Project, funded by the European Research Council and affiliated with Oxford University and the University of Washington, analyzed the role Twitter played in the American presidential election and found that Trump enjoyed a significant – one might even say yuge – advantage on the platform. Following the second presidential debate, pro-Trump hashtags generated roughly twice the traffic of pro-Clinton hashtags. And while most of that traffic seems to have come from real users based on frequency and times of tweets, a third of pro-Trump tweets seem to have come from bots, compared to only a fifth of pro-Clinton tweets. Interestingly, following the December 19, 2016, attack on a Christmas market in Berlin, dozens of Twitter accounts suspected to be bots switched from posting pro-Trump messages to posting attacks on Chancellor Angela Merkel. German Justice Minister Heiko Maas has gone so far as to suggest that Facebook be treated as a media company, meaning it would be legally accountable for its content.

This could foreshadow a particularly ugly Bundestag campaign in September. AfD has already made common cause with the American president-elect; its leaders have publicly praised him for both his policy preferences and his ability to beat the “establishment politicians” at their own game, and they have cited his surprise victory as proof that they might achieve the unthinkable and unseat Merkel. They seem to be taking up some of his tools, too: In October, Alice Weidel, a member of the AfD’s national leadership committee, told ZEITmagazin, “Of course we will include social bots in our election strategy. For a young party like ours, social media tools are essential to broadcast our positions to voters.”

Weidel later retracted her statement, saying the party would use social media tools – including social media analytics programs – but would abstain from using bots. But there are some indications that it has already broken that promise: On November 16, for example, dozens of accounts, many of them newly created, simultaneously posted an identical message with the slogan “Merkel muss weg” (Merkel must go) and a link to a YouTube video promoting an anti-Merkel protest organized by the AfD.

Professor Philip Howard, the lead researcher behind the Computational Propaganda Project, already observed evidence of this same pattern around the Brexit vote. Between June 5-12, his team sampled 1.5 million tweets with hashtags related to the referendum; of those 1.5 million, a third – 500,000 tweets – were generated by only one percent of the 300,000 accounts, strongly suggesting that they were programmed bots. Brexit bots were roughly three times as active as pro-Remain bots.

Bots aside, the various social media channels – Facebook in particular – upend traditional theories about how social movements are formed, which can help to explain why once-fringe movements like AfD, UKIP, and the Trump campaign are so surprisingly adept with these media. Helen Margetts, director of Oxford University’s Oxford Internet Institute, writes that social media “allows new, ‘tiny acts’ of political participation (liking, tweeting, viewing, following, signing petitions and so on), which turn social movement theory around. Rather than identifying with issues, forming collective identity and then acting to support the interests of that identity – or voting for a political party that supports it – in a social media world, people act first and think about it (or identify with others) later, if at all.”

Read more in the Berlin Policy Journal App – January/February 2017 issue.