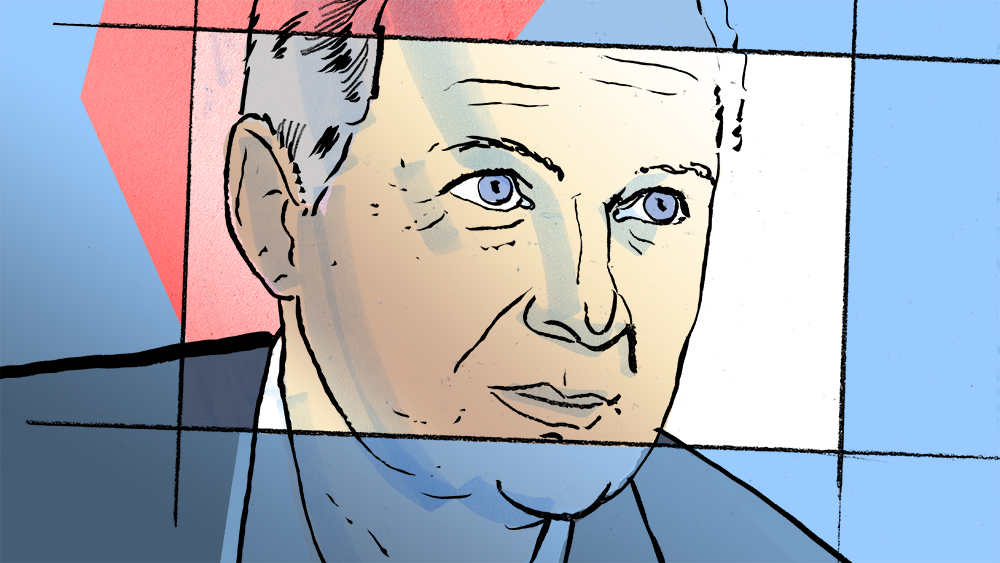

A 48-year-old veteran of French center-right politics has been tasked with putting France’s financial house in order. Having failed implementing reforms a decade ago, will he now inspire his compatriots to put country before politics?

Le renouveau, c’est Bruno. There’s a nice ring to the phrase in French. Bruno stands for renewal. It was with this slogan – reproduced on flyers, posters, and T-shirts – that Bruno Le Maire launched his 2016 campaign for the primary that would determine the center-right’s presidential candidate. Le Maire’s instinct was correct. The French were fed up with their political class, with the old parties, with generations of managers succeeding each other decade after decade. They wanted change, renewal. “I’ll torpedo the old regime; torpedo the technocrats, because I am one of them. … I’ll screw the old guard – that’s what’s at stake in 2017,” he said.

Despite the premature gray in his hair, Le Maire does not have to force himself to act young. Born in 1969, he is barely 48 years old. It seems he thought that showing up at the first primary debate without a tie would date his competitors, but television viewers did not agree. What he considered fashionable was taken as a sign of offhandedness. Le Maire finished fifth with just 2.4 percent of the vote. It was a major blow to a man who – only two years before – had defied former President Nicolas Sarkozy by winning a thirty percent vote share for the center-right leadership.

Another presidential hopeful, independent Emmanuel Macron, came up with an identical diagnosis of French public opinion. Macron had not run in any of the primaries, neither on the right nor on the left, but soon came to dominate the renewal niche. Macron flourished where Le Maire failed. The latter now finds himself the finance minister of the former. Le Maire’s old political friends cry treason. But he calls them the traitors.

“They betrayed the values of the right: keeping one’s word.” This was a veiled reference to François Fillon, winner of the conservative primary, who was under investigation on suspicion that his wife and children had been paid taxpayer money for bogus jobs. Fillon promised to drop out if he were charged, but failed to do so. “I asked him to withdraw for the good of our political family because we all knew that he was going to lose. I was true to my values,” Le Maire said.

After his own loss in the primary, however, Le Maire was the first to rejoin Fillon’s campaign against Alain Juppé as a spokesman for international affairs, then the first to leave him after the candidate’s legal troubles began, and yet again the first to offer his services to Macron after the latter’s victory made him France’s youngest-ever president. Both see the advantages of appointing Le Maire to head the economy and finance ministry. It allows the president to drive yet another wedge into the political right; and it spares Le Maire a stint of five or even ten years in opposition – a prospect that must have seemed incompatible with his ambitions.

Path to the Top

Well-born Bruno Le Maire is a prime specimen of France’s right-wing aristocracy, a product of France’s meritocratic grandes écoles and a so-called egghead. As a child he attended the private Paris primary school Les Moineaux, which embraced the Hattemer method, a pedagogical movement that shaped some of France’s most celebrated figures including the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Later, at the Jesuit school Saint-Louis de Gonzague, he sang in the children’s choir, performing for Pope John Paul II in 1980. Next came the École normale supérieure, where he finished at the top of his class with a thesis on statutory law in Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, passing the punishingly competitive agrégation – the national examination for entry into the ranks of elite teachers.

From here he proceeded to the École nationale d’administration, which paved the way for him to join the staff of then Foreign Minister Dominique de Villepin. Le Maire prides himself on having drafted the famous speech that his boss delivered at the UN Security Council in February 2003 arguing against US intervention in Iraq.

Le Maire followed Villepin to the Hôtel Matignon when Jacques Chirac made him prime minister. It was here that Le Maire weathered the storm surrounding a 2006 law that sought to loosen the youth labor market by waiving minimum wage requirements, among other things. Young people took to the streets in force, particularly university students. Then Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy, who was already picturing a future in the Elysée Palace, saw Villepin as a potential competitor and gave underhand support to the demonstrators. Ultimately, Chirac retreated and the law was shelved. “Already in 2005, I was appalled by the level of youth unemployment,” Le Maire said later. “I thought it would be a good idea to take specific action. We messed up.” He had learned a crucial lesson about the immense difficulty of pushing through reforms in France.

One might wonder if he has ever thought about leaving politics to devote himself to a literary career. His political experiences are recounted in Des hommes d’Etat (Of Statesmen, 2008), followed in 2013 by Jours de pouvoir (Days of Power). Written in his acclaimed literary style, the portraits he draws of his peers are hardly flattering. In 2012 he published a novel about the conductor Carlos Kleiber – Musique absolue : une répétition avec Carlos Kleiber (A Rehearsal with Carlos Kleiber) – a deep reflection on history, music, and politics. Young Bruno’s literary beginnings were somewhat less distinguished: As a high school student he penned spicy romance fantasies under the pseudonym Duc William. Even his more serious books have their racier passages: for example, his account of some erotic attentions from his wife administered in a hotel bathtub in Venice – which later inspired pointed jibes from Sarkozy.

Sarkozy’s presidency in 2007 nonetheless brought Le Maire an appointment as minister of European affairs. Finally he had the opportunity to make use of the German he acquired on a high school exchange in Bremen. However, this particular post happens to be the one where office holders serve the least amount of time – and the one with the highest turnover rates. By 2011, Le Maire had his eye on the finance ministry. Instead, Sarkozy put him in charge of agriculture.

No “Major Incompatibility”

By now, Le Maire had plunged fully into politics. He won his first seat in the Assemblée Nationale in 2007 as a representative the first constituency of Eure, a department west of Paris where his grandmother had a home. Elected first on a Union pour un mouvement populaire (UMP) ticket, later renamed Les Republicains, he was re-elected in June 2017 with Macron’s party La République En Marche! (LREM).

Evoking what he called the trauma of April 21, 2002 – the night extreme right-wing candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen made it into the second round of voting in that year’s presidential elections – Le Maire declared his support for Macron against Marine Le Pen immediately after the first round of presidential voting in April 2017, while a number of his political “friends” remained hesitant.

Now his mandate is to promote the economic policy of a French president who claims to be on neither the right nor the left. Le Maire says he sees no “major incompatibility” between his own views and Macron’s program – that is, “nothing prohibitive.” Their shared goal is to modernize how the state functions, to reduce public spending (currently at 56 percent of GDP), to reduce burdens on business, to simplify standards, and to make labor laws more flexible.

Beyond these general formulations, however, there are indeed notable differences between the program Le Maire embraced as a center-right primary candidate and Macron’s approach. The latter wants to increase social contributions by augmenting the flat tax on all income (CSG) to finance a reduction in payroll taxes; Le Maire was opposed. Macron wants to maintain the current level of the inheritance tax; Le Maire wanted to lower it. Macron has called for adjusting the wealth tax; Le Maire sought to suppress it altogether. Macron seeks to cut 120,000 government jobs; Le Maire had half a million cuts in mind.

A French Schäuble?

But for the new finance minister, method hardly matters. France is suffering massive unemployment (11 percent of the population and double that among young people); its national debt is nearing 100 percent of GDP; its budget deficit is well over the 3-percent mark set by the EU’s Maastricht Treaty. The previous government opened the floodgates on public spending before leaving office – a classic move on the eve of a French election. Le Maire wants the serious moral backing of the new powers. It would please him to be seen as a “French Schäuble.” He wants to work together with German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, much in the same way Macron is showing off his close relationship with Chancellor Angela Merkel. Both know well that France will not be able to play a guiding role in Europe unless it puts its financial house in order. “I am not making a totem out of the 3 percent mark,” Le Maire recently told Le Figaro. “I am making it a symbol: of renewed credibility in the eyes of our European partners.”

Macron prefers the word “transformation” over “reform,” and Le Maire has no objection to emulating him. He once spoke of blowing the system sky high. He did not manage it with his friends on the right – sometimes for lack of a majority and often for lack of courage. Now he is ready to try it with a young man under forty, who undoubtedly makes him feel old but who is nonetheless helping him realize one of his ambitions – perhaps while waiting for something better.

Even as he promotes budgetary rigor, Le Maire is doing something to correct his reputation as a technocrat who is unresponsive to social turmoil. (The very same Le Maire as a primary candidate railed against l’assistanat – the welfare state – and advocated limiting benefits.) “The liberal line cannot be the alpha and omega of the right’s political project,” he said after his defection to Macron’s LREM party. “A modern program for the right must reconcile liberty with solidarity.” He even intervened in his new role to try to save troubled private businesses and jobs threatened by international competition.

Thirty of Les Republicains’ eighty lawmakers have chosen to follow Le Maire’s example and support Macron and his government’s objective of avoiding pointless partisan quarrels. “I prefer my country to my party,” the recruits claim. “Je préfère mon pays à mon parti.” The slogan has a nice ring to it in French.