In the coming years, and all across the world, AI will shape politics, the economy, and society. It will also disrupt international affairs.

There are many other networks in the world… But the internet is a network that magnifies the power and potential of all others.” When Hillary Clinton, then US Secretary of State, tried to explain the importance of the internet for foreign and security policy in January 2010, many experts thought it was a waste of time. Should this really be a priority of US foreign policy? After all, as the general thinking went, there were more important issues, like the earthquake in Haiti or global terrorism.

Over eight years later, after the revelations of Edward Snowden, the digital offensive of the so-called Islamic State and the debate over “fake news,” hardly anyone is dismissing the internet as a distraction from serious foreign policy—even if many no longer regard the internet as a great blessing. (Clinton herself discovered the Internet’s dark side in the most painful of ways during the 2016 presidential election.) Foreign policy without the internet is no longer conceivable. This shift in opinion should be a warning to all those who today dismiss another technology as irrelevant for foreign policy: Artificial intelligence (AI). Just as the internet has pervaded politics, the economy, and society over the last ten years, AI will in the next ten years appear everywhere and disrupt everything. Any country that tries to ignore this development will lose relevance.

Looking around the Berlin foreign-policy world and beyond, one quickly gets the impression that for many people, AI is still uncharted territory. People either think it’s a new buzzword from California —“Yesterday it was Big Data, right?” Or they spread the word that the world’s going under. Soon, they say, AI will create an all-powerful super intelligence that will try to subjugate humanity, like in the action movie “Terminator.”

Better than Humans

Misperceptions like this are based on an incomplete understanding of what AI actually is. It is often confused with full (strong) Artificial intelligence which is seen as superior to human thinking. But that will remain Science Fiction for the foreseeable future or even forever. The AI of today is better understood as a “collective intelligence”: it is often about the digital extraction of data created by humans. Machine learning, a category into which nearly all important AI technologies fall, usually has two stages. First, neural networks—statistical systems inspired by the human brain—are fed vast amounts of data (for example cat pictures), so that they learn to recognize patterns (what cats look like). Then in the second stage, new data is presented, to which the networks apply what they have learned. Simply put: unlike other software, AI code isn’t written by programmers, but by data.

Thanks to the huge computational power of cloud computing firms like Amazon and Microsoft, AI services can often already recognize objects and language better than humans can. The best facial-recognition software already has 99 percent success rate at identifying faces, though only in laboratory conditions. Language recognition services achieve results that are nearly as good. Other programs can comfortably read scrawled handwriting, once they’ve digested about a hundred pages of it.

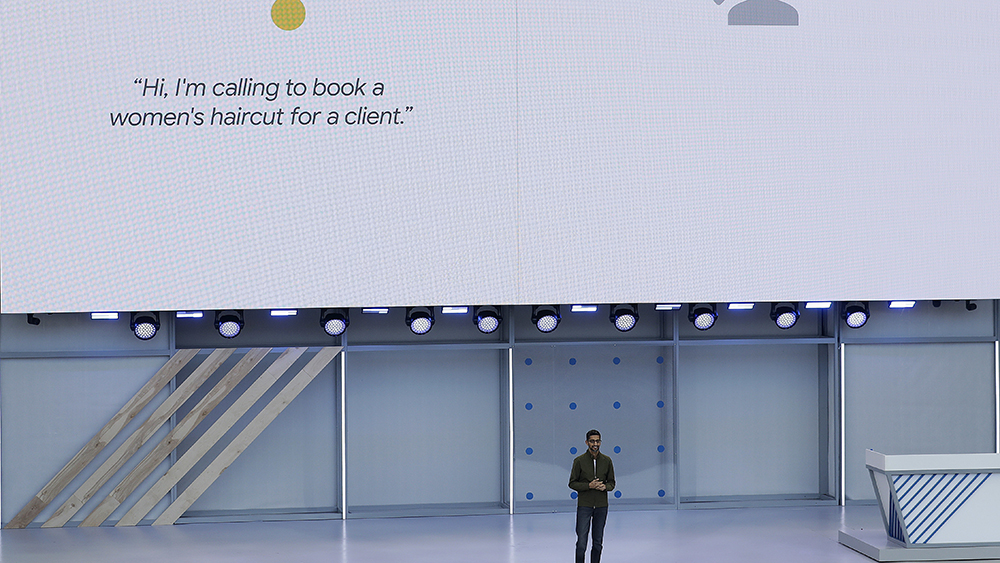

Companies can apply basic services like this to complicated tasks, as online-giant Google showed at a conference in California in May. Its latest AI-design, Google Duplex, was able to book a haircut appointment on the phone without the other person realizing that he was talking to a machine. For this demonstration, Google had to combine at least three AI services: language recognition, sentence understanding, and word formation.

AI as a Growth Factor

Big technology firms dominate the AI industry. They possess the most and the best data, programmers, and computer systems. But recently other businesses have begun to make use of AI, too. For example, the clothing retailer H&M uses it to detect fashion trends. Unilever, a producer of household and consumer goods, utilizes AI to evaluate job applicants. The energy company Repsol wants to use AI to make its refineries more efficient, while Siemens is using it to optimize the operation of its gas turbines.

It’s hard to predict how much growth AI will create. But the figures will not be small. Accountants from PricewaterhouseCoopers estimate that by 2030, AI will increase world economic output by 16 trillion dollars—more than China and India combined generate today. That figure is about five times the German GDP. According to Ajay Agrawal, Professor at the University of Toronto and author of the new book “Prediction Machines,” the most important economic effect of AI is that it will sharply reduce the cost of prediction, thus making businesses more productive. Just as electricity made light much cheaper—prices soon became 400 times cheaper than at the start of the 19th century—AI will make it much easier to look into the future.

“AI is like electrical power,” experts say. One day it will be used everywhere. And it’s only a matter of time until that is also the case in foreign and security policy—and in the German foreign ministry. But in what form? In a study released in early 2018, the Berlin think tank Stiftung Neue Verantwortung (SNV) identified three focal points: autonomous weapons, economic effects, and consequences for democracy and society.

Autonomous weapons, which take decisions on their own with the help of AI, are perhaps the most threatening consequence of technological development. They can take various different forms, from automated hacker attacks to self-controlling drone swarms. They raise a number of difficult questions, not least how much control of these systems humans can and should have. Arms experts in the US fear ethical asymmetry above all: countries like China could complete dispense with the “human in the loop,” while Western states potentially refuse to cross this red line.

After long internal discussions, Google decided in May to end its participation in Project Maven, a Pentagon program to develop software that can distinguish between people and things in images made by drones. For Chinese firms like Alibaba and Tencent, there are few concerns about such programs, because these companies are already involved in the “civil-military fusion,” as the government in Beijing calls its close cooperation with tech firms.

AI‘s Impact on Policy

As far as the economic consequences of AI are concerned, the effects on foreign policy are hard to evaluate. The technology could help some countries skip over entire levels of development. China wants to become the world leader in the industry and plans to build an AI-economy worth nearly 60 billion a year by 2030. Other countries will lose out, Germany probably among them. The country is considered a straggler. There are fears everywhere that many jobs will be lost, though such fears are probably exaggerated. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that only five percent of all professions can be automated away using currently known technology (though machines could do part of the work for more than half of all activities).

The question of economic concentration comes up more and more: Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple are already dominant worldwide, and AI could make them even more powerful. Denmark’s decision to send an ambassador to Silicon Valley was dismissed in many capitals as a publicity stunt, but it could prove to be forward-thinking.

AI’s impact on democracy and society will likely present major challenges for foreign policy. The internet has already shown that human rights and technology don’t always fit together. While Hillary Clinton in 2010 praised “the network of all networks,” the NSA used it to wiretap masses of people worldwide, as the revelations of former NSA employee Edward Snowden showed a few years later.

AI makes these “Snowden contradictions,” as the authors of the SNV study call them, even more clear. The technology isn’t just the perfect surveillance tool: video cameras equipped with special chips already follow people automatically. AI can also be used for mass manipulation that goes well beyond the most recent disinformation campaigns. American researchers recently discovered that the Chinese government is the source of nearly 450 million online comments per year whose main goal is to distract. Most of them are still written by humans, but in the future more and more artificially intelligent bots could be used.

As well as such fundamental problems, practical issues arise. Data is the most important raw material for AI. China possesses the world’s deepest data pool, especially when it comes to consumers. The country’s 772 million internet users are open to new things and ideas: many of them don’t carry cash in their wallets and only pay with their smartphones. Other countries, particularly Germany, are much poorer in data for cultural and legal reasons. In the future, data, like other resources, may be managed on a national level. And data protectionism is an ever-growing problem for global firms, as the Financial Times recently reported. The number of laws that forbid firms from exporting data has nearly tripled in the last ten years.

Finally, there’s the question of how the German foreign ministry and related institutions will themselves use AI. A study published in June by the British think tank Chatham House lays out three possible applications for governments: AI could create models of international negotiations, thus simplifying them; it could predict geopolitically important events; and it could help assess compliance with international arms control treaties. At least in the last two cases, we are no longer talking about the future. Record Future, a Swedish-American firm, is already using machine learning for early recognition of hacker attacks and other threats. And software from Palantir, a Silicon Valley firm partially funded by the Pentagon, helps inspectors from the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in their work in Iraq.

Germany the Laggard

How can politics react to all these challenges? A good AI foreign policy begins with a good AI domestic policy. A number of countries have made this key technology a national priority and published detailed strategy plans. Among them are the US and China, but also France, South Korea, and even smaller countries like Finland. By contrast, the government in Germany—a country that struggles with digitalization in general—has only now begun to seriously engage with the issue.

In terms of the development and use of AI, Germany is average at best. According to a response to a parliamentary inquiry, the federal government spends about 27 million Euros a year promoting AI research, which appears quite low compared to other developed nations, though there are no exact figures for comparison. And with few exceptions, German companies are not at the front of the pack: in early 2018, the Expert Committee on Research and Innovation came to the conclusion that other countries are “much more dynamic” in many areas of AI.

Not being a pioneer means that Germany can learn from other countries’ experiences, the SNV argued in a separate paper published in early June (“Cornerstones of a national strategy for AI”). The federal government, the study said, should have greater ambitions than just better promotion of individual AI technologies. Rather, it “should focus on building and supporting a strong, internationally competitive AI ecosystem.”

In short: we need a stool with lots of legs. Promoting research is certainly one of them, but probably not the most important. More important is a strong base. AI competence can’t only be taught in computer science; it also has to be included in other courses of study. Sufficient computational power and venture capital have to be more easily available. Instead of concentrating on the quantity of data, as China and the US do, Germany should prioritize the quality of data, since smaller quantities of relevant, well standardized data often achieve better results. If the mixture is right, an ecosystem like this will create competitive AI services—faster than would government research programs.

For foreign policy, guidelines for action still need to be written. But some basic principles are already clear. The most important is that going it won’t work. Germany is too small to keep up with the competition on its own. Germany strategy has to be integrated into a European strategy. The most obvious partner is France, which is already much farther ahead in terms of developing and using AI.

Competition for Top Talent

Germany also has to figure out which sort of AI it wants to stand for. There’s a lot of space between China’s state-capitalism approach and the American data monopolies, and that’s where Germany can make its name. It’s not just about the ethics of using AI, but about a new, smart operating system for the data economy. How can markets be organized around this unusual resource? How can personal data be anonymized? Should people be paid for the data they create?

The answers will also have consequences for the labor supply. AI is about computational power and, of course, data, but without a critical mass of data experts, Germany will struggle to keep up with the rest of the world. Attracting and keeping these people is not just a question of salary, although that area can’t be neglected. Even OpenAI, a non-profit organization in Silicon Valley, pays its top scientists almost two million dollars a year. It’s more important that Germany is considered an attractive AI location. There are implications for foreign ministries, too: if you don’t attract or train employees with AI skills, you will become less important.

The foreign-policy impact of the internet, described early on by Hillary Clinton, took a long-time to become clear. But then the internet showed its global political impact with full force. It will probably be the same with artificial intelligence. Foreign-policy specialists should be prepared, if they don’t want to play catchup.