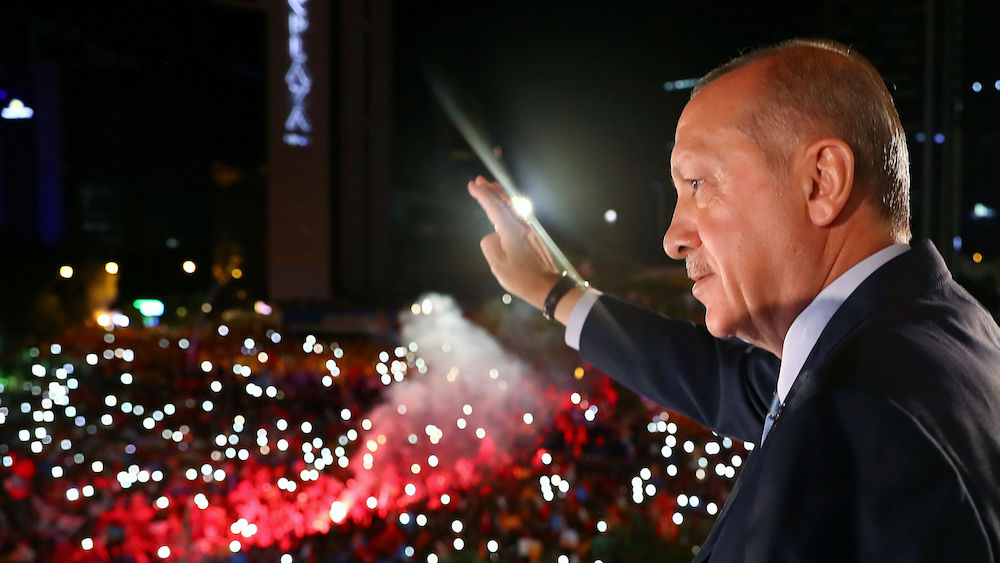

With this victory, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan will assume extensive presidential powers—but the Turkish opposition still has something to build on.

Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) claimed victory on Sunday night in Turkey’s pivotal elections, securing five more years at the helm of Turkish politics. Following a historic election season, which showcased a resurgent opposition for the first time since Erdoğan’s rise in 2002, the result defied expectations of a serious challenge to AKP supremacy.

The AKP’s long-standing secular rival Republican Peoples’ Party (CHP) believed they had fielded a winner in Muharrem İnce, who drew vast crowds to his campaign rallies and stole Erdoğan’s populist thunder as an everyman. Meanwhile, Meral Akşener of the İYİ Party (“Good Party”) promised to outflank the AKP and its coalition partner led by Devlet Bahçeli, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) from the right, attracting nationalist and conservative votes.

But while pre-election surveys had predicted that İnce would force Erdoğan into a run-off in the presidential contest, Erdoğan defeated his challenger with 52.6 percent of the vote to his opponent’s 30.7 percent. Meanwhile in the parliamentary poll, the AKP-MHP coalition received a combined total of 53.6 percent of the vote (against the opposition “Nation” Alliance’s 22.7 percent), which translates into a comfortable majority in the legislature.

With the presidency in hand, Erdoğan will also hold all levers of the state. His victory places him in command of an empowered executive presidency, approved in a controversial constitutional referendum in April 2017. An opposition-controlled parliament would have been the only check on his powers. Now fortified by a parliamentary majority, President Erdoğan will face very few—if any—obstacles in his quest for complete control over Turkey.

Here are the most important takeaways from the elections.

It’s the Economy…Again and Always

Turkey’s once-booming economy—formerly a major source of Erdoğan’s popularity—is now on the verge of a bust. The lira may have gained in early morning trading the day after the vote (June 25), but the factors that plague the economy still remain.

A key area is interest rates. The president does not want to raise them, because doing so would conflict with his method of growth. A reduction in rates brings him lower borrowing costs, which in turn makes it easier to borrow capital to channel towards his mega-projects, such as Istanbul’s “third” Yavuz Sultan Selim bridge, or the city’s massive new airport, which will be six times the size of London’s Heathrow. These projects may deliver tangible, short-term results, but they do not contribute to sustainable growth.

In fact, they have already put the economy in danger of overheating. The lira has depreciated 20 percent since the start of this year, and will soon start tumbling again. As inflation rises further into double-digits, the cost of living will continue to skyrocket. The current account deficit is $60 billion per annum, and foreign debt is almost $453 billion.

With an economy that runs on borrowing and investments, Turkey needs foreign money to repay this debt. But reserves are running low. In the first five months of 2018, foreigners only bought $118 million worth of Turkish equities and government bonds—a 97 percent drop compared to the same period last year. The volume of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) has also sunk to its lowest level in a decade.

Much will depend on whom Erdoğan appoints to oversee Turkey’s economy—and whether that person changes the country’s economic direction. Turkey needs higher-interest rates to cool off its “overheated” economy and to transition into a production-oriented economy that prioritizes agricultural development and long-term investment. And the backsliding in Turkey’s democracy needs to stop: This is crucial if the leadership wants to regain the confidence of financial markets and attract vital foreign funding. But if Erdoğan strengthens his grip on monetary policy—as he said he would ahead of the vote—the future looks bleak.

Erdoğan at the Mercy of Nationalists

The AKP’s support has actually decreased since the last election. Its share of the vote went down to 42.4 percent from the 49.5 percent it received in November 2015.

As a result, Erdoğan can now command a parliamentary majority only through a coalition with the MHP (unless he moves to form a coalition with any of the other opposition parties, which is very unlikely). In a way, the ultra-nationalist Bahçeli is the real winner of these elections. Expected to win less than 8 percent ahead of the vote and having barely held any rallies, his party won over 11 percent. The president will now need Bahçeli’s support to make sure parliament does not become a stumbling block, which means the MHP leader will be at the center of Turkish politics for the foreseeable future. Erdoğan, however, has argued for years that coalition governments are unstable governments, so it remains to be seen whether he will move to capsize this equilibrium.

The Opposition: A Mixed Success

In contrast to the CHP’s previous performances, İnce’s campaign contained elements that made him more popular within conservative circles. For the first time, the party and its top candidate stopped operating as representatives of the strictly secular and the metropolitan elite. As a result, İnce managed to score 30.5 percent, breaking through the CHP’s recent average of 25 percent. This is an important achievement.

Still, not everything went his way. İnce failed to draw the support of those who had voted “no” in the referendum, including a critical percentage of AKP supporters who were feeling “Erdoğan fatigue” and were ready to break away from Turkey’s long-time leader. The results show that many of these disgruntled voters shifted their allegiance to Erdoğan’s coalition partner, the MHP, but did not cross over to support the “other” side.

Once labeled the dark-horse of the race, Akşener also underperformed. Her party, an off-shoot of the MHP, was expected to collect support from traditional MHP voters unhappy with their party’s partnership with the AKP. Analysts also expected that her right-wing credentials would make her attractive to disillusioned AKP voters. But she only scored 7 percent in the presidential race and 10 percent in the parliamentary poll, down from the anticipated 12 percent and 13-17 percent ahead of the vote, respectively.

In the end, an electoral season that lasted just seven weeks—Erdoğan had surprisingly brought the election forward by eighteen months—was not enough for these two relatively unknown figures to win over the factions within the “Erdoğan camp” unhappy with the status quo and ready for change.

With Erdoğan dominating the airwaves, manipulating the power of incumbency as well as the resources of the state, İnce and Akşener faced an uneven playing field that stacked the odds heavily against them. Television is a powerful medium in politics, especially in Turkey. According to a study released ahead of the vote, 50 percent of AKP and MHP supporters either do not have internet access or do not use it on a daily basis. These voters live in a bubble tightly sealed with Erdoğan’s cult of personality. As long as this repressive environment persists, outreach will be difficult.

Where Do We Go from Here?

The elections showed that Turkey remains a polarized society, almost divided in half. And Erdoğan’s reliance on the nationalists suggests that the president is unlikely to push for “reconciliation” with the opposition and pull the country together. His nationalist partners have spoken against moving forward on the Kurdish peace process, supported extending the state of emergency imposed after the failed coup attempt of July 2016, and traditionally been reluctant to improve relations with the West.

However, even with Erdoğan on top, the spirit of democracy is not dead. The parliament now includes seven parties, representing almost every political movement. It is Turkey’s most diverse legislature in decades. This is the result of energetic opposition campaigns that united the center-left with the center-right, the Kurds with the nationalists, and the secular with the more religiously-minded. Driving attendance by the millions, these campaigns symbolized the undying resolve of those who want a return to liberal democracy.

The anti-Erdoğan camp needs to continue to harness this yearning, and keep the president on the back foot. For the next round is just around the corner—local elections are due in March 2019.